Votre panier

Il n'y a plus d'articles dans votre panier

Liste des produits et biographie de Champion Jack DUPREE

Chanteur de blues américain

Voir la biographie

Chamion Jack Dupree

Petit, râblé, buriné, cabossé... Champion Jack Dupree, qui a trimballé pendant plus de trente ans à travers tous les pays d'Europe une silhouette truculente et familière, était bien autre chose que certains bluesmen dont l'horizon ne dépasse guère la scène ou le cabaret. Certes, il s'exprimait par le vecteur du blues avec les rudiments de piano qu'il avait appris durant son enfance, mais sa philosophie de la vie, sa vivacité d'esprit, son intelligence, dépassaient de très loin l'image folklorique et pittoresque qu'il pouvait donner, la caisse de bière sous le piano ou esquissant un pas de danse comique tout en continuant à marteler le clavier. Représentation superficielle qui cachait un être sensible, curieux, ouvert et cultivant son jardin secret : la peinture qu'il pratiquait dans la même veine "primitive" et colorée que son piano et ses chants.

On dit que William Thomas Dupree naquit le 4 juillet 1910 — il n'en était pas bien sûr lui-même — à la Nouvelle-Orléans, cinquième enfant d'un père originaire du Congo belge et d'une mère créole Cherokee. Il est encore bébé quand ses parents meurent dans un incendie et est placé dans un orphelinat, la Colored Waif's Home for Boys, là même où le jeune Louis Armstrong avait usé ses fonds de culotte quelques années auparavant.

C'est là que le petit "Jack", comme on le surnomme, s'initie au piano. À l'âge de 14 ans, il quitte l'établissement et commence à traîner dans le French Quarter. Il y rencontre les pianistes Tuts Washington et surtout Willie Hall, dit "Drive 'em Down", figure légendaire de Rampart Street qui disparaîtra vers 1930 sans avoir jamais laissé la moindre trace sur disque. Jack se lie d'amitié avec ce personnage, joue et chante avec lui dans les barrelhouses du quartier et se réclamera toujours de son influence. Il fréquente aussi les orchestres de Papa Celestin, Chris Kelly, Kid Rena, se produit dans les clubs locaux et s'entraîne à l'école de boxe de Rampart Street.

Mais dès 1927, il avait commencé à vadrouiller un peu partout : dans le Midwest, sur la Côte Est et jusqu'à Chicago. Jack Dupree mène ainsi une vie de hobo au gré des rencontres, gagnant principalement sa vie comme boxeur professionnel — 107 combats, paraît-il, entre 1932 et 1940 — et accessoirement comme chanteur, danseur, pianiste, entertainer dans les house parties de Chicago ou les speakeasies de la Nouvelle-Orléans.

Dupree s'était marié à 22 ans avec une certaine Ruth, "artiste" comme lui, avant de choisir comme port d'attache en 1935 Indianapolis où il a le temps de rencontrer, quelques mois avant sa mort, Leroy Carr (cf. EPM/Blues Collection 159062). Après le décès de ce chanteur-pianiste qui le marquera profondemment, il joue très souvent avec le guitariste Scrapper Blackwell, ex-compagnon de Carr, et fréquente les musiciens locaux, le chanteur Little Bill Gaither, Jesse Ellery et Wilson Swain entre autres. Vers 1939/40, le duo vocal qu'il forme avec la chanteuse Ophelia Hoy dans la tradition du vaudeville est l'une des attractions du Cotton Club d'Indianapolis.

C'est également en 1939 que Dupree, en visite à Chicago chez Tampa Red, fait la connaissance de tout le gratin du blues de la Cité des Vents : Big Bill Broonzy, Jazz Gillum, Roosevelt Sykes, Curtis Jones... Ce qui conduit le producteur Lester Melrose à lui organiser une séance pour OKeh en juin 1940 (1). Trois autres suivront durant l'année 1941 pour lesquelles le "Champion", comme il a été surnommé en raison de ses exploits pugilistiques, fait venir ses amis d'Indianapolis Wilson Swain et Jesse Ellery (parfois orthographié Edward ou Eldrid), superbe et méconnu guitariste électrique avec qui il se produit régulièrement (voir l'annonce d'un concert où il accompagne Jack et Ruth Dupree au Lincoln Theater de la Nouvelle-Orléans).

Le pianiste, qui circule dans les régions du Midwest et de New York, quitte définitivement Indianapolis à la mort de son épouse avant d'être, en 1942, mobilisé dans l'US Navy en tant que... cuisinier ! Il participe ainsi aux opérations du Pacifique et est fait prisonnier par les Japonais. Il restera au moins un an en captivité au Japon, probablement jusqu'en 1944 si l'on se réfère aux dates de ses enregistrements (il avait gravé quelques faces à New York en 1942 avec Sonny Terry et Brownie McGhee).

De retour dans la Grosse Pomme, Jack Dupree est embauché comme cuisinier à l'Université de Harlem et commence à intégrer la vie musicale de ce quartier où existe une scène du blues souterraine (Alex Seward, Big Chief Ellis, Stick McGhee, Larry Dale, etc.) que fréquentent toujours Terry et McGhee pourtant admis dans les cabarets branchés de Broadway. Il enregistre quelques 78 tours par-ci par-là vers 1944/45 pour Asch, Solo, Continental, Lenox, puis rencontre Joe Davis qui lui offre la possibilité de publier de nombreux disques en solo entre avril 45 et mars 46 et l'aide à démarrer enfin une véritable carrière professionnelle. Dupree va donc se produire régulièrement pendant des années dans les petits clubs new yorkais (Ringside Bowl, 125th Street Club, Long Island, Spotlight Club, Mayfair Club, Italian Frank's...) et poursuivre une copieuse carrière discographique, souvent sous le couvert de pseudonymes, pour de nombreux petits labels : Alert (46), Abbey (49), Apex et Gotham (50), Derby (51), Harlem (52), Red Robin (53), accompagnant aussi son voisin d'immeuble Brownie McGhee.(2)

De locale, la renommée du Champion va s'étendre progressivement lorsque le chanteur va signer avec des maisons plus importantes comme Apollo (1949/50) et surtout King (1951/55) chez qui il décroche son "tube", Walking The Blues qui, à partir d'août 55 va rester cinq semaines au Top Ten R&B de la revue Billboard. Ce succès lui ouvre les portes du fameux Apollo de Harlem et lui permet de participer à des tournées prestigieuses à travers le pays en compagnie de vedettes comme Little Willie John, Marie Knight, Hal Singer, Nappy Brown ou B.B. King. Il enregistre alors pour Groove, filiale de la Victor et, de 1957 à 1959, monte son propre orchestre avec lequel il demeure plus ou moins en résidence au Celebrity Club de Freeport (NY).(3)

Un superbe album pour Atlantic en 1958... puis Jack profite de l'intérêt que le Vieux Continent commence à manifester pour le blues pour franchir l'océan et effectuer une tournée en Angleterre en 1959. On connaît la suite : Champion Jack Dupree sera le premier bluesman à s'installer définitivement en Europe, là où il rencontrera sa dernière épouse, apprendra à lire et à écrire (en un an !), se mettra à la peinture et effectuera une longue et fructueuse carrière qui le conduira sur les scènes de tous les pays et qu'il ponctuera d'une trentaine d'albums. Résidant en Angleterre, au Danemark, en Suisse, en Suède, c'est à Hanovre, où il avait passé les quinze dernières années de sa vie, qu'il s'éteindra le 21 janvier 1992. En 1990, invité par le New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, il était revenu dans sa ville natale pour la première fois depuis trente-cinq ans.

Champion Jack Dupree était à la fois un bluesman profondément ancré dans la tradition — il pratiquait un jeu de piano robuste, très instinctif qui s'appuyait sur des basses boogie rustiques — et atypique dans la mesure où il combinait l'apport néo-orléanais ancien avec le style urbain sophistiqué de Leroy Carr et de Peetie Wheatstraw dont il perpétuait l'esprit sarcastique. Très amusant sur scène, conteur pourvu d'un bagoût d'improvisateur inépuisable, il pouvait, à cause de cette facette extravertie (celle de l'entertainer), donner une image de lui un peu superficielle. Mais elle ne doit pas cacher une réelle profondeur ; Dupree était concerné par les problèmes sociaux, raciaux et politiques sur lesquels il pouvait s'exprimer. C'est pourquoi ses blues se démarquent souvent du "fond commun" habituel du répertoire. Dès ses premiers enregistrements, il aborde le problème de la drogue, ce qui à l'époque n'est pas courant, dans Junker Blues (bâti sur une structure de 8 mesures typiquement néo-orléanaise dont Fats Domino — The Fat Man — et d'autres se souviendront) et évoque la prison dans Chain Gang Blues. Ses rapports avec les femmes sont souvent traités avec humour mais il dépasse les éternels jeux de mots et double sens (I'm A Doctor For Women). Attentif aux évènements, et avant de réagir à la mort de Martin Luther King en 1968, il avait déjà rendu hommage au Président Roosevelt, celui qui avait sû rendre espoir à la communauté noire durant les années sombres de la Grande Dépression, dans F.D.R. Blues :

«Je me sens si triste

Les larmes coulent sur mon visage.

J'ai perdu un grand ami

Qui faisait honneur à notre race.» (4)

À sa manière, Jack Dupree fut un témoin de son peuple, son œuvre le montre et ses amis peuvent l'attester.

Jean Buzelin

Notre amitié avec Champion Jack Dupree, qui va durer trente ans, commence dès son arrivée en Suisse en 1961. Il était devenu tellement un membre de notre famille qu’il m’est difficile de séparer l’homme du musicien. Mais l’homme était le musicien. Tout est dans ses chansons, comme Jean Buzelin a si bien démontré. Mes souvenirs de Jack ressemblent à sa musique et ses tableaux: pleins de couleur, de chaleur et de vie. Son sens de l’humour irrésistible! Il rigolait tellement à ses propres histoires qu’il avait du mal à en arriver à la fin…sortant de sa poche ce gigantesque mouchoir blanc pour essuyer les larmes de rire qui coulaient à flots.

Et puis sa superbe cuisine — les concerts “American Folk Blues Festival”, organisés par Lippmann & Rau à Zurich au début des années 60, se terminaient souvent par un énorme “gumbo” chez Jack, histoire de renouer, et parfois “jammer”, avec ses anciens compagnons de route, perdus de vue depuis son départ des Etats-Unis.

Bien sûr, au fil des années, nous avons tous connu des moments difficiles mais Jack refusait toujours de se laisser abattre, encourageant les autres d’agir de la même façon. You can make it if you try (Tu peux y arriver si tu le veux) n’était pas seulement le titre d’une de ses chansons les plus émouvantes, mais aussi son credo. Même après une douloureuse intervention chirurgicale en 1989, il a continué à se produire sur scène presque jusqu’à sa mort, portant souvent un de ces bandeaux indiens qu’il fabriquait lui-même et son immense sourire toujours sur son visage!

Sa disparition en 1992 n’a pas seulement privé Don et moi-même d’un très cher ami et nos filles de leur “black Daddy”, mais nous avons perdu autre chose: Champion Jack Dupree fut le premier à nous avoir appris ce que voulait vraiment dire feelin’ that feelin’. (“sentir le blues”).

Joyce Waterhouse

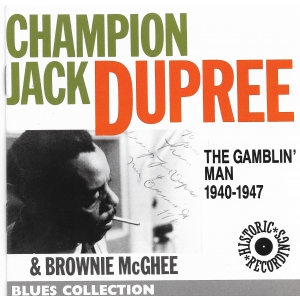

CHAMPION JACK DUPREE - THE GAMBLIN’ MAN (1940-47)

Champion Jack Dupree, his small, stocky figure, topped by the craggy, battered face, a familiar sight to European audiences for over thirty years, was much more than a mere bluesman whose horizons are bound by the show business scene. Of course, he expressed himself through the blues with the piano rudiments he learnt as a child, but his philosophy of life, his wit, his intelligence went far beyond his flamboyant and picturesque image: the crate of beer under the piano, the dance steps executed while still banging away at the keys. This superficial exterior hid a very sensitive man, interested in and open to many things and cultivating his own secret garden, painting, his pictures echoing the “primitive” colours of his piano and songs.

William Thomas Dupree’s date of birth is generally given as 4 July 1910—but he wasn’t absolutely sure himself within a year or so—in New Orleans, the fifth child of a Belgian Congo father and a Cherokee Creole mother. He was still a baby when his parents died in a fire and he was placed in the “Coloured Waifs’ Home for Boys”, the same orphanage where Louis Armstrong had grown up a few years earlier.

It was here that little “Jack”, as he was nicknamed, started to play piano. He left the home at the age of fourteen and started to hang around the French Quarter where he met pianists Tuts Washington and especially Willie “Drive ‘em Down” Hall, the legendary Rampart Street figure who died around 1930, leaving no recorded trace of his work. Jack became his friend, playing and singing with him in local barrelhouses and he always acknowledged how much he learnt from this old-timer. He also frequented the bands of Papa Celestin, Chris Kelly, Kid Rena, appeared at local clubs and trained at the Rampart Street boxing gym.

But by 1927, he had started to hobo around: in the Midwest, on the East Coast and as far as Chicago, mainly earning his living by boxing—he claimed to have fought 107 bouts between 1932 and 1940—and occasionally as singer, dancer, pianist, general entertainer at Chicago house parties or in New Orleans speakeasies.

At the age of 22, Dupree married a certain Ruth, also a performer, with whom he settled in Indianapolis in 1935. It was here that he met piano-vocalist Leroy Carr a few months before his death (see EPM/Blues Collection 159062) who had such a profound influence on Dupree’s vocal phrasing. After Carr’s death, he often played with the latter’s old partner Scrapper Blackwell, and met up with local musicians such as singer Little Bill Gaither, Jesse Ellery and Wilson Swain. Around 1939/40 he formed a very successful vaudeville-style vocal duo with singer Ophelia Hoy which became a star attraction at the Indianapolis Cotton Club.

It was also in 1939 that, while visiting his friend Tampa Red in Chicago, Dupree met some of the biggest blues names in town: Big Bill Broonzy, Jazz Gillum, Roosevelt Sykes, Curtis Jones… With the result that producer Lester Melrose organised a session for OKeh in June 1940 (1). Three others followed in 1941 to which the “Champion”, as he was now known as a result of his boxing exploits, invited his Indianapolis friends, Wilson Swain and Jesse Ellery (sometimes written Edward or Eldrid), a relatively unknown but gifted electric guitarist with whom he regularly appeared (see ad announcing Jack and Ruth Dupree’s appearance at the New Orleans Lincoln Theater).

After the death of his wife, Jack, who had continued to circulate around the Midwest and New York, finally left Indianapolis before being drafted into the US Navy in 1941…as a cook! He was taken prisoner during the Pacific campaign, spending at least a year in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp (whence his superb Japanese imitations!). Probably until 1944, if his recording dates are anything to go by (he had cut several sides in New York in 1942 with Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee).

Back in the Big Apple, he got a job as cook at Harlem University and gradually began to integrate the local underground blues scene (Alex Seward, Big Chief Ellis, Sticks McGhee, Larry Dale etc.) which was also still frequented by Terry and McGhee even though they now had access to the “in” clubs on Broadway. He recorded the odd 78s around 1944/45 for Asch, Solo, Continental, Lenox, before meeting Joe Davis who gave him the opportunity of recording several solo records between April 45 and March 48 and helped him to start out finally on a professional career. As a result Dupree appeared regularly for many years in small New York clubs (Ringside Bowl, 125th Street Club, Spotlight Club, Mayfair Club, Italian Frank’s…) and continued to record extensively, often under another name, for countless small labels: Alert (46), Abbey (49), Apex and Gotham (50), Derby (51), Harlem (52), Red Robin (53), also accompanying Brownie McGhee who, at the time, was living next-door to Jack.(2). The Champion’s reputation increased as he signed up with bigger recording labels such as Apollo (1949/50) and especially King (1951/55), with whom he made his hit Walking The Blues which, from August 1955, stayed in the R&B Top Ten of Billboard magazine. Success that led him to Harlem’s famous Apollo Theater and on to top-class tours throughout the country, in the company of such stars as Little Willie John, Marie Knight, Hal Singer, Nappy Brown or B.B. King. He next recorded for Groove, a Victor subsidiary, and from 1957 to 1959 led his own band which had a more less permanent residency at the Celebrity Club in Freeport, New York. (3).

After a superb Atlantic album in 1958, Jack decided to try his luck in Europe, where interest in blues was growing, and went on a tour of England in 1959. He was the first bluesman to settle permanently in Europe where he met his last wife, learned to read and write (in about a year!), took up painting and enjoyed a long and fruitful career, taking him to many countries and during which he cut some thirty albums. After living in England, Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden, he spent the last fifteen years of his life in Hanover, where he died on 21 January 1992. He returned to his birthplace only once in thirty-five years, on the invitation of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival in 1990.

Champion Jack Dupree was a bluesman both firmly rooted in tradition—his robust, instinctive piano playing relied heavily on left-hand boogie rolls—and yet atypical in that he combined the old New Orleans style with the more sophisticated, urban approach of Leroy Carr and Peatie Wheatstraw, perpetuating the latter’s sarcastic wit. Extremely funny on stage, a gifted story-teller with a seemingly unending supply of jokes, this extrovert image of an “entertainer” may suggest a certain superficiality which was far from the truth. The interior man was deeply concerned by social, racial and political problems which is why his blues stand out from the normal, habitual repertory. In his earliest recordings he tackled the drug problem, which was unusual at the time, in Junker Blues (a typical New Orleans 8-bar structure that Fats Domino—The Fat Man— and other musicians later took up) and evokes prison in Chain Gang Blues. His relationships with women are often treated humorously but are not merely the eternal play on words or double meanings (I’m A Doctor For Women). Politically aware, before reacting to the death of Martin Luther King in 1968, he had already rendered homage to President Roosevelt, who gave hope to the black community during the dark days of the Depression, in F.D.R. Blues.:

“I sure feel bad,

With tears running down my face,

I lost a good friend,

Was a credit to our race”

In his own way, Jack Dupree was a witness to his people as his work shows and his friends can vouch for.

Adapted from the French by Joyce Waterhouse

With special thanks to Jacques Demêtre for the loan of his 78s and to Joyce Waterhouse for her photos and documents.

Notes:

(1) According to Jack Dupree himself, it is Scrapper Blackwell, who is supposed to have made the trip as well, on guitar on Gamblin’ Man; this is doubtful as discographers mention Bill Gaither. Yet, this excellent singer only played guitar occasionally, so…?

(2) The closing sides on the present album are the very first of Jack as accompanist. Contrary to what has sometimes been written, he never played on Lil Green’s first recordings; indeed, the delicate technique of Simeon Henry has little in common with Jack’s much more elementary and earthy playing.

(3) See the account by Jacques Demêtre and Marcel Chauvard, illustrated with numerous photos, describing their meeting with Jack in New York in 1959, Land of the Blues (CLARB/Soul Bag, Paris 1994).

From the time of his arrival in Switzerland in 1961, Jack Dupree became so much part of our family and remained so for 30 years that it is difficult for me to separate the man from the musician. But then the man was his music. It’s all there in his lyrics as Jean Buzelin has so clearly demonstrated. My memories of Jack are like his music and his paintings: full of colour, warmth and life. That irresistible sense of fun! An inimitable raconteur, he would laugh so hard at his own jokes that he could barely get to the punch line…and out would come that vast, white handkerchief to wipe away the tears of uncontrollable mirth!

Then his superb cooking — the Lippmann & Rau “American Folk Blues Festival” concerts in Zurich in the early 60s usually ended up with a huge gumbo at Jack’s place giving him a chance to meet up, and maybe jam, with old friends he hadn’t seen since leaving the States.

Inevitably during such a long friendship we all had our tough times too, but Jack had an amazing ability to bounce back and encourage others to do the same. You Can Make It If You Try was not only the title of one of his most moving songs, it was also his creed. Even after undergoing major surgery in 1989, and in spite of ever-increasing pain, he continued to appear in public until shortly before his death, often sporting one of his home-made Indian headbands and with that huge grin still splitting his face!

With his death in 1992, Don and I lost not only a dear friend and our daughters their “black Daddy”, but something much more special: Champion Jack Dupree was the very first to show us what feelin’ that feelin’ really meant.

Joyce Waterhouse

Less