Votre panier

Il n'y a plus d'articles dans votre panier

Liste des produits et biographie de Julia LEE

Chanteuse de blues américaine

Voir la biographie

JULIA LEE

Plus que n'importe lequel de tous ces noms illustres qui sont nés, ont grandi, fait leurs premières armes ou connu la gloire à Kansas City, celui de Julia Lee appartient à cette grande cité du Mid-West. Sa vie, son métier et sa carrière sont totalement liés à cet endroit fameux et béni pour tous les musiciens qui, durant les années 20, 30, 40, y trouvaient autant de travail qu'ils le voulaient et participaient à l'extraordinaire émulation suscitée par cette ville tapageuse du Missouri, laquelle, grâce aux manœuvres plus ou moins légales du potentat local Tom Pendergast, était moins touchée que d'autres par la prohibition et la crise économique.

C'est dans cette ambiance pétaradante qu'une forme de jazz mainstream s'est développée, représentant une sorte de point d'équilibre entre les racines sudistes de la musique noire (et donc nourrie de blues) et les développements les plus avancés du jazz orchestral new yorkais. Aucun professionnel ne pouvait éviter Kansas City (musicien, organisateur, directeur artistique, producteur de disques, journaliste). "Vaut le voyage", aurait écrit le Guide Vert musical de l'époque s'il avait existé. Mais y habiter, comme Julia Lee depuis les premières années du siècle, c'était encore mieux ! C'est dans la région, à Boonville (Missouri), que Julia Lee voit le jour le 31 octobre 1902. Son père, George Lee Sr, joue du violon et la petite, dès l'âge de 4 ans, pousse facilement le couplet au milieu du string trio que dirige papa. En 1912, la famille déménage à Kansas City et Julia, qui vient de se faire offrir un piano, commence à étudier l'instrument auprès des professeurs Scrap Harris, un ancien élève de Scott Joplin, et Charles Williams. À partir de 14 ans, Julia joue à l'église, dans les house parties, les fêtes scolaires, les patinoires, les réunions mondaines... et se fait remarquer dans les spectacles d'amateurs. Vers 1918, alors qu'elle vient de se marier à 16 ans, elle parfait son éducation musicale à l'université. Julia Lee commence à jouer du piano professionnellement au Novelty Club de Kansas City puis, à partir de 1920, sa carrière va se confondre pendant treize ans avec celle de son frère, George E. Lee. Saxophoniste, George Ewing Lee Jr (1896-1959) a débuté à peu près en même temps que Bennie Moten, le premier grand chef d'orchestre de Kansas City. Il commence d'abord par former un trio au Lyric Hall avec sa sœur puis étoffe progressivement son équipe avec des musiciens locaux, Clarence Taylor (saxes), Thurston Maupin (trombone) puis Sam Utterbach (trompette). Le George E. Lee's Band se produit dans les clubs de la ville et effectue des tournées dans tout le Sud-Ouest. Une parenthèse : Julia Lee, chanteuse, aurait gravé deux tests pour OKeh en 1923 mais on n'en a jamais trouvé trace. En 1927, le George E. Lee & His Novelty Singing Orchestra enregistre deux faces pour la petite marque Meritt à Kansas City alors qu'un pianiste-arrangeur vient de rejoindre la formation. Il s'agit de Jesse Stone qui fera parler de lui plus tard lors des grandes heures du rhythm and blues chez Atlantic. Vers 1928, ils jouent au Reno Club, le lieu où se retrouvent les meilleurs musiciens de la ville (Count Basie, plus tard, en sera le principal pensionnaire). En novembre 1929, l'orchestre, devenu un tentette avec notamment l'arrivée de saxophoniste Budd Johnson, enregistre six faces pour Brunswick. Jesse Stone tient toujours le piano sur les disques et le frère et la sœur se partagent les vocaux, Julia chantant en soliste He's Tall Dark And Handsome et Won't You Come Over To My House. Ce seront là les ultimes traces discographiques d'une formation qui n'aura jamais atteind la notoriété ni sans doute la qualité des big bands réputés de la ville bien que des gens comme Buck Clayton ou Jimmy Rushing en aient laissé d'excellentes appréciations et qu'occasionnellement Chu Berry, Lester Young et Charlie Parker n'auront pas dédaigné "tailler un bœuf" avec l'orchestre. Elle est aussitôt engagée en soliste au Milton's Tap Room, endroit qui restera son port d'attache jusqu'en 1948. Un bail de quinze ans dans ce club chic où, appétissante à souhaits à 40 ans passés dans sa robe de dentelle noire et avec des fleurs dans les cheveux, elle charmait la clientèle (exclusivement blanche) où l'on pouvait apercevoir Benny Goodman, — le "Roi" venait à Kansas City sans doute pour prendre quelques leçons de swing ! — la chanteuse Mildred Bailey et son mari Red Norvo dont le xylophone saupoudrera plus tard quelques jolis disques de Julia (Mama Don't Allow It, I Was Wrong). À demeure au Milton's, la pianiste-chanteuse s'en échape parfois pour honorer quelqu'engagement à Chicago au Three Deuces avec le batteur Baby Dodds et au Offbeat Club avec le trompettiste Wingy Manone en 1939, au Beachcomber de Omaha (Nebraska) et au Downbeat Room de Chicago en 1943. En novembre 1944, pour la première fois depuis quinze ans, Julia Lee se retrouve derrière des micros d'enregistrement accompagnée cette fois par le septette de Jay McShann. La chanteuse reprend son Come Over To My House et propose sa version du classique Trouble In Mind qui a repris récemment un coup de jeune avec Sister Rosetta Tharpe. L'été suivant, Julia grave enfin ses premières faces sous son nom avec l'orchestre de Tommy Douglas et quelques autres transfuges de chez McShann dont Sam "Baby" Lovett, le batteur favori de Pete Johnson, qu'elle avait connu dans l'orchestre de son frère et qui figurera dans tous ses disques jusqu'en 1949. C'est la rencontre avec Dave Dexter, rédacteur en chef de Down Beat et chargé du département jazz/blues de la jeune marque Capitol, qui s'avère décisive. Convoquée à Los Angeles en août 1946, Julia Lee enregistre Gotta Gimme What'cha Got, un boogie sur un rythme endiablé qui préfugure le rock 'n' roll, lequel entre dans les charts en novembre. C'est le début du succès populaire pour une femme de 44 ans mais qui, fraîcheur vocale et dynamisme musical aidant, peut sans problème cacher son âge et faire figure de jeune chanteuse ! Ainsi lancée, dans une période charnière où le R&B naissant reste encore fortement marqué par la couleur jazzy des petits ensembles swing, Julia Lee va connaître plusieurs années fastes, enregistrant pour Capitol de nombreux disques à succès à Los Angeles puis à Kansas City jusqu'en 1952. Mais cette soudaine célébrité ne la grise pas. Et même si elle participe avec Baby Lovett à un gala à la Maison Blanche en présence du président Truman en 1948, même si elle honore quelques engagements dans des clubs de l'Ouest (le Ciro's et le Tiffany de Los Angeles en 1949, le Rossonian Club et le Theater Lounge de Denver en 1950), elle décline les tournées que, promotion oblige, les artistes se doivent d'accomplir. Elle assure un second hit avec Snatch And Grab It en octobre 1947, réalise sa meilleure vente avec le blues salace King Size Papa en janvier 1948 (250.000 ex.) et obtient plusieurs autres réussites commerciales (dont I Didn't Like It The First Time, Chhristmas Spirit et Tonight's The Night reproduits ici), You Ain't Got It No More obtenant même la neuvième place au Top Billboard R&B en novembre 1949. Réussites musicales également car la plupart de ses chansons sont de petits bijoux. Il faut dire que la chanteuse-pianiste est fort bien accompagnée par ses Boy Friends que dirige Lovett auxquels se joignent volontiers des solistes de renom comme le trompettiste Ernie Royal (Snatch And Grab It, Bleeding Hearted), le tromboniste Vic Dickenson (Mama Don't Allow It), le saxophoniste Benny Carter (le même titre et I Was Wrong, King Size Papa, I Didn't Like It...)... sans oublier des musiciens à la réputation plus modeste comme le trompettiste Geechie Smith (Gotta Gimme What'cha Got, That's What A Like, King Size Papa) ou le sax-ténor Dave Cavanaugh (Gotta Gimme..., Snatch...) dont les solos ne pâlissent pas à côté de ceux de leurs illustres voisins de pupitre.

Après ces quelques années de reconnaissance tardive et inattendue, Julia Lee se contente à nouveau des projecteurs plus modestes du Cuban Room puis du Hi-Ball Bar, clubs locaux où elle officie souvent même si elle enregistre encore quelques faces entre 1954 et 1958 et apparait dans le film «The Delinquents» en 1957 avec le trio du batteur Bill Nolan. Le 8 décembre 1958, une attaque cardiaque fatale la surprend pendant son sommeil. La gloire ne l'avait pas intéressé de son vivant, sa disparition engendrera un oubli complet pendant près de vingt-cinq ans jusqu'aux premières rééditions d'une partie de son œuvre.

Julia Lee possède une voix fraîche, souple, riche, bien placée, on sent qu'elle ne s'évapore pas avec les bulles du champagne que sirotent les noctambules venus l'entendre. La bonne femme a les pieds sur terre. C'est une chanteuse robuste, incarnée, équilibrée, drôle, truculente et qui passait pour avoir une bonne descente. Très coquine, elle excelle dans les chansons aux paroles audacieuses qui fourmillent d'allusions (I Didn't Like It The First Time, Do You Want It ?), s'appuient sur le double-entendre (King Size Papa, Tonight's The Night) ou affichent ouvertement leur caractère sexuel (Gotta Gimme What'cha Got, Snatch And Grab It), et elle n'hésite pas à fustiger l'incompétence du partenaire au plumard (Don't Come Too Soon, You Ain't Got It No More). C'est aussi une pianiste "robuste et féminine" au sens où pouvait l'être sa concitoyenne Mary Lou Williams qui l'appréciait beaucoup, Count Basie également. En complément naturel et nécessaire à son chant et à son jeu de piano qui s'appuie volontiers sur de solides basses boogie, la musique de Julia Lee est également fraîche, très enlevée et rythmée, swinguante au possible mais non légère. Les racines sont solides, aussi peut-elle reprendre Bleeding Hearted Blues ou Mama Don't Allow It en en faisant des chansons de son époque. En fait de toutes les époques car sa musique, pourtant rapidement écrasée par les rythmiques appuyées, les interchangeables solos de saxo ténor et la guitare électrique du rhythm and blues des années 50, a beaucoup mieux vieilli, ne s'étant jamais enfermée dans un schéma formel stéréotypé. Jean Buzelin

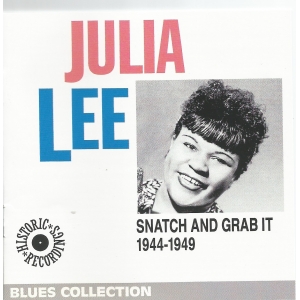

JULIA LEE-SNATCH AND GRAB IT (1944-1949)

Among the many illustrious names of those who were born, grew up and became famous in Kansas City, that of Julia Lee stands out. Her life and career are inextricably linked to this famous Mid-Western city. A city where, in the 20s, 30s and 40s, musicians could find as much work as they wanted, becoming part of the rowdy life of a town that was the envy of others for, thanks to more or less legal methods employed by the mayor, Tom Pendergast, it was less affected by prohibition and economic problems.

It was in this explosive atmosphere that a form of mainstream jazz sprang up, a balance between the Southern roots of black music (based on the blues) and the more advanced developments in New York orchestral jazz. While the “Big Apple” was certainly the “jazz capital”, even if only on a business level, no professional could avoid Kansas City (musicians, promoters, artistic directors, record companies, journalists). If a Michelin guide to jazz had existed at the time, Kansas would certainly have received the mention “worth a detour”. But to live there, as Julia Lee did, from the beginning of the century, was even better!

Julia Lee was born in Boonville, Missouri, on 31 October 1902. Her father, George Lee Sr. played violin and, from the age of four, she sang with his string trio. In 1912, the family moved to Kansas City where Julia, who had just been given a piano, started lessons with Scrap Harris, an old pupil of Scott Joplin and Charles Williams. By the time she was fourteen, Julia was playing in church, at house parties, school fetes, ice rinks, fashionable parties etc. and became noticed on talent shows. Around 1918, having just got married at the age of sixteen, she went to university to finish off her musical education. She began to play piano professionally at the Novelty Club in Kansas City and then, from 1920 on, her career was to be linked for thirteen years with that of her brother, George E. Lee.

Saxophonist George Ewing Lee Jr. (1896-1959) made his debut about the same time as Benny Moten, the first important Kansas City bandleader. He started out by forming a trio at the Lyric Hall with his sister, gradually filling out his group with local musicians: Clarence Taylor (saxes), Thurston Maupin (trombone), then Sam Utterbach (trumpet). The George E. Lee’s Band appeared at local clubs as well as touring throughout the South-West. Incidentally, it appears that Julia Lee cut two test sides for OKeh in 1923 but no trace of them has ever been discovered.

In 1927, George Lee & His Novelty Singing Orchestra recorded two sides for the small Meritt label in Kansas City. Pianist-arranger Jesse Stone, later to make a name for himself on Atlantic rhythm and blues recordings, had just joined the band. Around 1928, they played at the Reno Club, where all the best musicians in town ended up (Count Basie would later become the principal in-house musician). In November 1929 the orchestra, now numbering ten with the arrival of saxophonist Budd Johnson, recorded six sides for Brunswick with Jesse Stone on piano and the brother and sister sharing the vocals. Julia sings solo on IHe’s Tall Dark And Handsome and Won’t You Come Over To My House. These sides are the last discographic traces of a formation that never achieved the reputation, nor perhaps the quality, of the reputed big bands around town, although they were appreciated by musicians such as Buck Clayton and Jimmy Rushing and occasionally Chu Berry, Lester Young and Charlie Parker were not above jamming with them.

Apart from a short stint with Benny Moten and an engagement at the Yellow Front Café in 1931 with New Orleans trumpeter Bunk Johnson, Julia Lee stayed with the orchestra until it broke up in 1933. She was immediately hired as a soloist at Milton’s Tap Room which remained her base until 1948. Fifteen years in this chic club where, in spite of her 40-odd years, she remained as attractive as ever in her black lace frock and with flowers in her hair, charming the exclusively white clientele that included Benny Goodman—the “King” doubtless in Kansas City to take some lessons in swing!—and singer Mildred Bailey and her husband Red Norvo whose xylophone can be heard on some of Julia’s later records (Mama Don’t Allow It, I Was Wrong). Although based at Milton’s, she occasionally took time off to fulfil engagements in Chicago at the Three Deuces with drummer Baby Dodds and at the Offbeat Club with trumpeter Wingy Manone in 1939, at the Beachcomber in Omaha, Nebraska, and at the Downbeat Room in Chicago in 1943.

In November 1944, for the first time in fifteen years, Julia Lee was back in the recording studios, accompanied this time by Jay McShann’s septet. The session included a repeat of her Come Over To My House and a version of the classic Trouble In Mind that had recently been given a new lease of life by Sister Rosetta Tharpe. The following summer, Julia finally cut the first sides under her own name with Tommy Douglas’ orchestra and other musicians from the McShann formation, including Sam “Baby” Lovett, Pete Johnson’s favourite drummer, whom she had first met in her brother’s band and who featured on her records until 1949. A good saxophonist, Douglas is said to have influenced Charlie Parker to a certain extent. For the first time we also hear the singer accompanying herself with great authority on piano on these two records which, however, were not particularly successful.

Then came the decisive meeting with Dave Dexter, editor of Down Beat and head of the jazz/blues department of the fledgling Capitol label. Invited to Los Angeles in August 1946, Julia Lee recorded Gotta Gimme What’cha Got, a boogie with an undeniable rock ‘n’ roll rhythm that made the charts in November. This was the beginning of popular success for a 44-year-old woman whose vocal freshness and musical dynamism helped her to hide her age and appear as a young vocalist!

Launched at the time of a musical turning-point, when R & B was still coloured by the jazzy tones of small swing ensembles, Julia Lee enjoyed several successful years, recording several hits for Capitol in Los Angeles and then in Kansas City right up to 1952.

But this sudden fame did not turn her head. Even though she appeared with Baby Lovett at a White House gala in 1948 in front of President Truman, even though she fulfilled several engagements in Western clubs (Ciro’s and the Tiffany in Los Angeles in 1949, Denver’s Rossonian club and Theater Lounge in 1950), she refused to tour, something that artists really have to do to retain their popularity originally based on records. She had a second hit with Snatch And Grab It in October 1947, achieved her highest sales with the saucy blues King Size Papa in January 1948 (250,000 records) and had various other commercial successes (among them I Didn’t Like It The First Time, Christmas Spirit and Tonight’s The Night included here). You Ain’t Got It No More even reached number nine in the Billboard R&B top ten in November 1949. Not only were these titles a commercial success but most of them are musical gems in their own right, on which Julia Lee is accompanied by her Boy Friends led by Lovatt, alongside some of the best soloists of the time such as trumpeter Ernie Royal (Snatch And Grab It, Bleeding Hearted), trombonist Vic Dickenson (Mama Don’t Allow It), saxophonist Benny Carter (the same title plus I Was Wrong, King Size Papa, I Didn’t Like It…)…without forgetting lesser-known musicians including trumpeter Geechie Smith (Gotta Gimme What’cha Got, That’s What I Like, King Size Papa) and tenor saxophonist Dave Cavanaugh (Gotta Gimme…, Snatch…) whose solos are up to the standard of those of their more illustrious peers.

After these years of late and unexpected recognition, Julia Lee returned to the less brilliant footlights of the Cuban Room and then the Hi-Ball Bar, local clubs where she played frequently, although she did record a few more sides between 1954 and 1958 as well as appearing in a film “The Delinquents” in 1957 with drummer Bill Nolan’s trio.

She died in her sleep from a sudden heart-attack on 8 December 1958. Fame had not interested her when alive and, after her death, she was forgotten for twenty-five years before part of her work was reissued.

Sparkling is the word that comes to mind when listening to Julia Lee. Sparkling, yes, but her clear, rich, relaxed voice has none of the ephemeral sparkle of the champagne drunk by the night-clubbers who flocked to hear her. Her feet were always firmly on the ground. She is a solid, heartfelt, easy, amusing and direct singer, with a good vocal range. She excels on titles whose lyrics are more than a little suggestive (I Didn’t Like It The First Time, Do You Want It?), making full use of double-entendre (King Size Papa, Tonight’s The Night) or overt sexual references (Gotta Gimme What’cha Got, Snatch And Grab It) and she does not hesitate to criticise an unsatisfactory performance in bed (Don’t Come Too Soon, You Ain’t Got It No More). She is also a “swinging, female” pianist, somewhat in the style of Mary Lou Williams who greatly admired her, as did Count Basie. She belonged to the same school. One could almost say that her playing encompasses Pete Johnson at one end and Fats Waller at the other, all of whom she preceded by several years!

Both Julia Lee’s singing and piano playing were based on solid boogie rhythms and her music swings tremendously but never unnecessarily. This enables her to take standards such as Bleeding Hearted Blues or Mama Don’t Allow It and transform them into songs for her own era. Yet, not only for her own era because her music, although pushed out by the heavy beat and crushing tenor sax and electric guitar solos of R & B in the 50s, has stood the test of time much better as it fitted no formal musical stereotype. Like that of Louis Jordan, it belongs to a jazz era when musicians could create a beat merely by tapping their foot and did not feel obliged to hammer it out.

In a way, listening to a song by Julia Lee is like listening to three minutes of choreography in sound!

Adapted from the French by Joyce Waterhouse

Less