Votre panier

Il n'y a plus d'articles dans votre panier

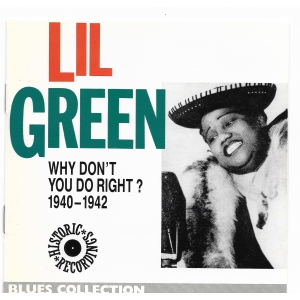

Liste des produits et biographie de Lil GREEN

Chanteuse de blues américaine

Voir la biographie

LIL GREEN

Pendant quelques années, elle fut peut-être la chanteuse la plus populaire du pays auprès de la communauté noire. Puis la musique changea. Le style à la fois précieux et incisif de Lil Green ne s'accommoda guère des sonorités puissantes et électriques du rhythm and blues. Alors on l'oublia. Les amateurs de blues comme ceux de jazz qui la connaissaient mal se renvoyèrent mutuellement la balle et, si son nom a fait de timides réapparitions dans les dictionnaires et encyclopédies, la littérature qui concerne la chanteuse est demeurée très faible. C'est vrai que, durant toute sa carrière, à l'exception peut-être d'un passage au Café Society, Lil Green ne chanta que pour le public noir et ses disques ne se vendirent qu'auprès de lui. Elle ne fut donc jamais récupérée par le circuit du jazz et mourut trop tôt pour être redécouverte par les jeunes amateurs de blues. Pourtant l'oeuvre enregistré de Lil Green, qui s'échelonne sur une brève période : 1940-1942 d'une part, 1945-1947 d'autre part, plus deux ultimes traces en 1949 et 1951, se situe à de très hauts niveaux, tant à celui de la qualité du répertoire (entièrement original) qu'à celui de l'accompagnement d'un goût parfait, qui favorisent l'éclatement du talent de cette grande chanteuse.

Née dans l'Etat du Mississippi (ou en Louisiane?) probablement le 22 décembre 1919, Lillian Green, comme ses neuf frères et soeurs, perd ses parents très tôt. Agée d'une dizaine d'années, elle doit se mettre au travail et quitter la maison. Arrivée à Chicago, elle parvient à suivre l'école, donne ses premiers concerts dans le cadre scolaire vers 1934 et travaille ensuite comme serveuse et chanteuse dans les clubs. Mais c'est dans d'étranges circonstances que R.H. Harris, le chanteur soliste des Soul Stirrers, fait la connaissance de Lil Green : " A cette époque, Lil était en prison pour avoir tué un homme lors d'une bagarre dans une taverne. Elle avait l'habitude de chanter tous les dimanches durant l'office à la prison et Harris s'y rendait chaque semaine afin de l'entendre chanter Sleep On, Mother et Is Your All On The Altar?" (*) Harris conservera une grande amitié pour la chanteuse qui, libérée, commence à acquérir une certaine réputation à partir des années 1938-39. Elle se produit notamment au Manchester Grill de Chicago l'année suivante et grave ses premières faces pour Bluebird en compagnie d'un trio dont le pianiste, très professionnel, au jeu complet, pertinent et délicat, ne peut être Champion Jack Dupree comme cela figure sur certaines discographies, mais très certainement l'excellent et méconnu Simeon Henry que l'on rencontre à la Nouvelle Orléans dès 1927 avec la chanteuse Florence White. Le guitariste, pilier des séances à Chicago, est Big Bill Broonzy. Ce jeudi 9 mai 1940, il vient d'accompagner le chanteur-harmoniciste Jazz Gillum et, juste après l'enregistrement de Key To The Higway (qui va devenir l'un des plus grands classiques du blues), il se met au service de Lil Green dont ce sont les premiers pas dans un studio.

Parmi les quatre titres gravés ce jour-là par la chanteuse, Romance In The Dark, une superbe ballade blusy, obtient immédiatement un succès considérable. En 1941, Lil Green est à l'affiche du Club 308 de Chicago et commence à effectuer des tournées avec son trio dont Big Bill est devenu le guitariste régulier : "J'ai été le guitariste de Lil Green durant trois ans, et j'ai aussi écrit des chansons pour elle, comme par exemple : My Mellow Man, Country Boy, Give Your Mama One Smile, et d'autres. En fait, ce n'est pas vraiment écrire que je faisais, je fredonnais la chanson jusqu'à ce que Henry, le pianiste, et le bassiste Ransom Knowling aient trouvé les bons accords. Après cela, elle chantait les paroles que j'avais préparées. Ransom et Henry étaient de bons musiciens et nous avons fait des tournées avec Lil Green dans tous les Etats du sud des USA ."(**) Durant l'année 1941, le chanteuse et son trio participent à trois séances d'enregistrement d'où sortent d'autres grands succès : le beau My Mellow Man, justement composé par Broonzy, et surtout le troublant blues en mineur Why Don't You Do Right? écrit par Joe McCoy sur le motif musical en douze mesures ABB (ABC pour les paroles) de Weed Smokers Dreams gravé par ses Harlem Hamfats en 1936, et dont Lil Green donne une bouleversante interprétation -le pouvoir émotionnel de cette chanson égale sans doute les meilleurs morceaux de Billie Holiday. L'année suivante, la chanteuse Peggy Lee effectuera ses débuts avec l'orchestre de Benny Goodman en reprenant Why Don't You Do Right? dans une version plus rapide et largement dédramatisée qui fera un triomphe et lancera sa carrière, d'où l'éternel refrain : de l'avantage d'être Blanc dans un monde dirigé et réglé par les Blancs.

Mais, pour son public, Lil Green est devenue une véritable vedette; elle remplit les grands dancings et salles de spectacle de Chicago, Détroit et New York et passe au Savoy Ballroom et au Café Society Downtown avec Ira Tucker, le futur lead vocal des Dixie Hummingbirds, en 1942 : "Evidemment, elle est devenue trop célèbre pour un petit groupement comme le nôtre, et elle nous a laissé tomber un à un. Ransom fut lâché après la troisième tournée et moi après la quatrième. Henry, lui, partit avec elle à New York, où elle le congédia pour se faire accompagner par un grand orchestre ."(**) Le grand orchestre en question est d'abord celui du batteur Tiny Bradshaw avec qui elle donne de fabuleuses soirées au Plantation Club de St. Louis, au Lido Ballroom de New York, à l'Elks Ball et au Gardens de Pittsburgh, au Tic Toc Club de Boston en 1943, au Royal Theater de Baltimore en 1944... Puis elle effectue une longue tournée dans le Sud avec la revue de l'orchestre de Luis Russell où figurent notamment le chanteur-tromboniste Clyde Bernhardt et les Deep River Boys, quartette vocal alors au sommet de sa popularité. Après le Petrillo Ban (la grève des enregistrements qui dura deux bonnes années), Lil Green retourne en studio en avril 1945 avec son nouveau trio (seul subsiste Simeon Henry), chante au Regal Theater de Chicago et à l'Apollo Theater de New York, en 1945 avec Tiny Bradshaw et en 1946 avec le big band du trompettiste Howard Callender qui devient son orchestre régulier : "Je suis allé voir Lil Green à l'Apollo en 1945 et 1946. Chaque fois, elle a été contente de revoir le vieux Bill, et je fus heureux de constater qu'elle n'avait pas oublié ceux qui avaient été à ses côtés dans ses début."(**)

Lil Green enregistre à quatre reprises pour Victor en 1946 et 1947 avec Callender, d'abord en big band puis avec des formations orientées vers les tendances musicales du Rhythm & Blues -on y entend notamment les saxophonistes Budd et Lem Johnson, le bassiste Al Hall, les batteurs Red Saunders et Denzil Best- et enfin avec un quintette à nouveau dirigé par Simeon Henry, mais elle ne peut se faire une place au milieu de ces nouvelles musiques tonitruantes et rythmiquement hypertrophiées, ne pouvant y exprimer sa nature réelle faîte de délicatesse, de séduction et de confidence. A la fin de la décennie, elle chante encore au Club De Lisa et Chez Paree à Chicago, ajoutant à ses blues un répertoire plus jazzy qui lui convient bien mais qu'elle n'arrive pas non plus à imposer. Sa popularité décline et, malgré un disque pour Aladdin en 1949 et un autre pour Atlantic en 1951 avec l'orchestre du pianiste Howard Biggs, elle tombe malade et n'a plus la force physique et morale pour redresser une situation qui la conduit à l'hopital en juillet 1953. Le 14 avril 1954 à Chicago, Lil Green meurt des suite d'une broncho-pneumonie. Elle allait avoir trente-cinq ans, un âge décidement fatidique dans le jazz.

Un peu plus jeune que Helen Humes, Rosetta Howard, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Billie Holiday, contemporaine de Ella Fitzgerald et Wee Bea Booze, légèrement plus âgée que Dinah Washington et Sarah Vaughan, où se situe donc Lil Green par rapport à ces chanteuses dont certaines font presque l'histoire de la musique vocale afro-américaine à elles seules? Stylistiquement et historiquement, elle représente un point d'équilibre parfait, un riche lieu de convergences entre feu le blues classique -elle prolonge dans l'esprit Bessie Smith malgré une voix de soprano beaucoup moins puissante-, le blues urbain traditionnel des Memphis Minnie et Merline Johnson -le splendide jeu de guitare de Big Bill Broonzy y est pour beaucoup-, le voisinage vocal avec Billie Holiday, non formel mais qui interroge: voix frêle, acide, coquine, sensuelle, érotique (comme l'a fait remarquer Gérard Herzhaft), admirablement placée, enfin elle semble tendre désespérément le témoin à Helen Humes, Dinah Washington, Ruth Brown, LaVern Baker...

Trop tôt ou trop tard? En fait Lil Green correspond parfaitement à son époque, cette irrémédiable charnière de l'Histoire, trop courte peut-être, et qui bascula emportée par la guerre et l'après guerre. La fragilité que semble dégager la chanteuse (pourtant bien enveloppée!), son expression par petite touches, le ton confidentiel de ses chansons ne pouvaient survivre. Le gros libre fut refermé, écrasant une délicieuse petite fleur. Quarante ans après, y a-t'il une place pour Lil Green? En feuilletant les pages du cruel manuel d'histoire, on devrait pouvoir y trouver quelques pétales séchés.

Jean Buzelin

La presque totalité des enregistrements réalisés par Lil Green entre 1940 et 1942 est ici rééditée pour la première fois en disque compact. Seuls cinq titres sur vingt-huit ont été écartés pour des raisons de moindre qualité sonore ou musicale et parce que l'ensemble aurait dépassé les limites de durée permises par le CD. Nous remercions Jacques Demêtre et Etienne Peltier pour les documents rares qu'ils nous ont confié.

(*) Anthony Heilbut, The Gospel Sound, Limelight Edition, 1985.

(**) Big Bill Broonzy et Yannick Bruynoghe, Big Bill Blues, Edition Ludd, Paris 1987.

For a few years, she was perhaps the most popular singer in the country with black audiences. Then the music changed. Her style, at once refined and incisive, did not really lend itself to the loud, electric sounds of rhythm-and-blues. So Lil Green was quietly forgotten. Blues and jazz fans ill-acquainted with her work for long took mutual refuge in the pretence that she belonged in the others’ camp. Even today, although her name has at last put in a timid reappearance in jazz dictionaries and encyclopaedias, literature on this grossly-neglected singer remains amazingly thin. True, during her entire career, with possibly the lone exception of her Café Society appearances, Lil Green performed, whether live or on record, exclusively for black audiences. Consequently, she was never picked up by the jazz circuit, and she died too young to benefit from the 1960s blues revival. And yet Lil Green’s recordings — made during three very brief periods: 1940-42, 1945-47 and a couple of final efforts in 1949 and 1951 — are of an amazingly high artistic level. Highlighted by a repertoire of originals and by backings of impeccable taste, the talent of this fine singer becomes immediately evident.

Born in Mississippi (or Louisiana?) on 22 December 1919, Lillian Green, along with her nine brothers and sisters, lost her parents at a very early age. Still barely ten, she had to leave home and start working. She later landed in Chicago, where, managing at last to put in some schooling, she gave her first concerts at school events around 1934. She subsequently worked as a waitress and singer in various clubs, but it was in strange circumstances that R. H. Harris, solo singer with the Soul Stirrers, then made her acquaintance. “At that time, Lil was in jail for killing a man in a roadhouse brawl,” recounts Anthony Heilbut in his book, The Gospel Sound. “She used to sing every Sunday during the prison church service, and Harris would go out each week to hear her do Sleep On, Mother and Is Your All On The Altar? ”. Harris maintained the friendship with Lil, who, once freed, began building up something of a reputation for herself. By 1938-39 she was already quite well known; and in 1940 not only did she play a significant engagement at Chicago’s Manchester Grill, but she also made her first records for Bluebird.

Her backing trio on this début date features a highly accomplished, very stylish pianist that cannot possibly be Champion Jack Dupree (as indicated by certain discographies), but is surely the excellent and all-too-little known Simeon Henry, first heard in New Orleans with singer Florence White in 1927. The guitarist, one of the main pillars of the Chicago studio scene, is Big Bill Broonzy, who on this 9 May 1940 had been accompanying singer-harmonicist Jazz Gillum. As soon as they had finished recording Key To The Highway (destined to become one of the great blues classics), Big Bill put his considerable talents at the disposal of the young girl-singer. Among the four titles she cut that day is Romance In The Dark, a superb ballad that immediately enjoyed immense success.

In 1941, Lil Green featured at Chicago’s Club 308 and began doing touring work with a regular trio built around Big Bill. “I was Lil Green’s guitarist for three years,” Broonzy has related, “and I also wrote songs for her, things like My Mellow Man, Country Boy, Give Your Mama One Smile and so on. I didn’t really write what I did, I just hummed it until Henry, our pianist, and bassist Ransom Knowling found the right chords. After that, she sang the words I’d prepared. Ransom and Henry were good musicians, and we toured all round the South with Lil Green.”

During the course of 1941, the singer and her trio undertook three further recording sessions, producing a number of new hits, among them the beautiful My Mellow Man and, especially, the disturbing minor-key blues, Why Don’t You Do It Right?. This latter piece was written by Joe McCoy based on the 12-bar ABB pattern (ABC for the vocal) of Weed Smokers’ Dreams, a number recorded by his Harlem Hamfats in 1936. Here, Lil Green turns in a breathtaking rendering of the song, no doubt the equal of Billie Holiday’s most moving work. The following year, Peggy Lee marked her début with the Benny Goodman orchestra by recording her own interpretation of Why Don’t You Do It Right?, a faster, less dramatic version that scored a big hit and set the singer upon the road to fame, hence once again confirming the old adage: better to be white in a white man’s world!

Nevertheless, for her audience, Lil Green was now a big star, capable of filling the largest theatres and ballrooms in Chicago, Detroit and New York. In the “Big Apple”, she featured at the Savoy Ballroom and Café Society Downtown, the latter engagement in 1942 pairing her with Ira Tucker, future lead-singer of the Dixie Hummingbirds. “Of course, she got too big for a little group like ours,” rued Big Bill, “and she dropped us one by one. Ransom was let go after the third tour, and me after the fourth. Henry went to New York with her, but she fired him to work with a big band.” The big band in question was that of drummer Tiny Bradshaw, with which she gave some fabulous performances at the Plantation Club in St. Louis, the Lido Ballroom in New York, the Elks Ball and the Gardens in Pittsburgh, the Tic Toc Club in Boston (1943) and the Royal Theatre in Baltimore (1944). Following all of which, Lil set off on an extensive tour of the South with the Luis Russell Orchestra revue, co-starring alongside singer-trombonist Clyde Bernhardt and the Deep River Boys vocal quartet, then at the very peak of their popularity.

After the Petrillo Ban (the more-than-two-year ban on recording imposed by the American Federation of Musicians), Lil Green returned to the studios in April 1945 with her new trio, pianist Simeon Henry the only survivor from earlier days. She sang at the Regal Theatre in Chicago and the Apollo Theatre in New York, backed by Tiny Bradshaw in 1945 and the big band fronted by trumpeter Howard Callender in 1946, the latter now set to become her regular outfit. Big Bill Broonzy recalled: “I went to see Lil Green at the Apollo in 1945 and 1946. Each time she was pleased to see old Bill, and I was glad to see she hadn’t forgotten the guys who’d been with her at the start.”

Lil Green recorded for Victor on four occasions in 1946 and 1947, backed by Callender first with a big band, then with groups turned towards Rhythm & Blues (featuring saxophonists Budd and Lem Johnson, bassist Al Hall, and drummers Red Saunders and Denzil Best), and finally with an outfit again led by Simeon Henry. But she was out of place in the context of this new loud, rhythm-laden music, which ill suited her delicate, seductive, intimate style. At the end of the decade, she was still singing at Chicago’s Club De Lisa and Chez Paree, adding to her blues programme some more jazz-oriented numbers, a successful mix from the artistic point of view, but one that did not make a big impact on her audiences. Her popularity went into decline and, despite an album for Aladdin in 1949 and another for Atlantic in 1951, she fell ill, now no longer possessing the physical or moral strength to mount a comeback. She was hospitalised in July 1953, and on the following 14 April 1954 she died in Chicago after an attack of bronchial pneumonia. She was in her 35th year, a decidedly cursed age in jazz.

A little younger than Helen Humes, Rosetta Howard Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Billie Holiday, a contemporary of Ella Fitzgerald and Wee Bea Booze, slightly older than Dinah Washington and Sarah Vaughan, where exactly does Lil Green fit in among such a posse of illustrious names? Stylistically and historically, she stands at a point of perfect equilibrium, a bustling crossroads of vocal blues and jazz. From one direction, she comes as an extension of the old classic blues (despite a light soprano voice much less powerful than that of Bessie Smith). From another, she brings the traditional urban blues of such artists as Memphis Minnie and Merline Johnson (thanks, to a great extent, to the splendid guitar of Big Bill Broonzy). From a third, she bears a certain resemblance to Billie Holiday (the frail, acidic, teasing, sensual, even erotic voice, and the admirable way she uses it). And striving to advance in a fourth direction, the convergence of the other three, she seems like some torch-bearer desperately reaching out towards the likes of Helen Humes, Dinah Washington, Ruth Brown and LaVern Baker.

Was it, then, that Lil Green arrived too early? Or perhaps too late? In fact neither, for she fits her time perfectly, a crucial time in history, but one all-too-quickly swept away by war and its swirling aftermath. Lil’s apparent fragility (despite that ample frame), her delicate approach and her intimate style could not possibly survive such turbulence. The great book was thus slammed to, mercilessly crushing a delightful little flower. Forty years on, is there still a place for Lil Green? Surely, as we flip through the pages of the cruel manual of history, we should welcome the chance to find a few dried petals.

Adapted from the French by Don Waterhouse

1987

Less