Memphis MINNIE / AND LITTLE SON JOE

VOUS RECEVREZ UN BON D'ACHAT 10% À PARTIR DE 40 € DE COMMANDE

Les enregistrements1-2 : Memphis Minnie (g,vo), Jimmy Gordon (p). Chicago 19353-4 : Memphis Minnie (g,vo), Black Bob (p), Will Weldon (steel g), Bill Settles (b) Chicago 19355 à 7 : Memphis Minnie (g,vo), Black Bop (p), Alfred Bell (tp). Chicago 19368-9 : Memphis Minnie (g,vo), Black Bob or John Davies (p), Fred Williams (dm),10 à 13 : Memphis Minnie (g,vo), unknown (p), Charlie Mc Coy (mand), unknown (b). Chicago 193814-15 : Little Son Joe : Little Son Joe (vo), Memphis Minnie (g), Fred Williams (dm). Chicago 1939 - 194016 – 17 : Memphis Minnie (g,vo), Little Son Joe (g), unknown (b) Chicago 194118 : Memphis Minnie (g,vo), Little Son Joe (g), Alfred Elkins (imb) Chicago 194119-20 : Memphis Minnie (g,vo), Little Son Joe (g), Ransom Knowling (b), Judge Riley (dm). Chicago 1946

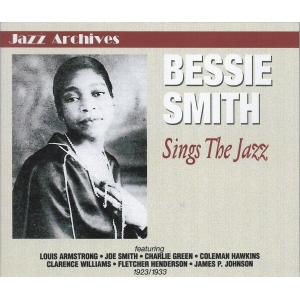

Au sein d'une société américaine puritaine et patriarcale où le poids moral, religieux, social, familial (sans parler de celui de l'argent) est très fort, les femmes noires ont été les dernières à bénéficier de l'émancipation. Et c'est dans ce milieu que grandit une petite bonne femme aux reins solides, au cœur bien accroché, à la langue bien pendue et n'ayant pas froid aux yeux, celle qu'un producteur "imaginatif" baptisa Memphis Minnie en 1929, du nom de la souris de Walt Disney, on se demande bien pourquoi ! Cette petite souris sortit du berceau le 3 juin 1897 à Algiers dans les environs de la Nouvelle Orléans. Elle s'appelait Lizzie Douglas et, quand elle eut 7 ans — l'âge de raison? — toute la famille (qui comptera treize enfants) s'installa à Walls dans le Mississippi. Lizzie guitariste du Memphis Jug Band. Mais c'est au sein du Beale Street Jug Band de Jed Davenport qu'elle rencontre le guitariste Joe McCoy avec qui elle convole en justes noces en 1929. Cette même année, le couple surnommé Kansas Joe & Memphis Minnie enregistre ses premiers disques à Memphis. Le morceau Bumble Bee devient un succès qui dépasse les frontières des états du Sud et, très vite, les duettistes vont gagner Chicago où, à partir de 1930, ils gravent de très nombreux disques et se produisent dans les meilleurs clubs de la ville. Mais en 1935 leurs routes divergent, McCoy prenant ombrage de la popularité de son épouse qui occupe de plus en plus le devant de la scène. Memphis Minnie (qui continuera à signer ses œuvres Minnie McCoy) a incontestablement l'étoffe pour mener sa carrière toute seule. Elle a 38 ans et sa réputation ne faiblira pas durant la dizaine d'années qui voit s'affirmer à Chicago un blues urbain directement issu de Sud profond et dont elle est une pièce maitresse. C'est cette période que nous avons choisi d'illustrer avec ce CD. Minnie joue alors au sein de formations typiques du Chicago Blues où figure souvent le pianiste Black Bob avec qui elle se produit au Tavern Hotel en 1936 (He's In The Ring, pièce consacrée à la figure afro-américaine la plus célèbre de l'époque, le boxeur Joe Louis, If You See My Rooster...). Mais elle réalise également de très beaux disques seule avec sa guitare qu'elle maîtrise parfaitement (Down In New Orleans, Hoodoo Lady...), ne s'aventurant que très rarement en dehors des canons du blues. Qu'un trompettiste, Alfred Bell, étoffe le groupe (Hot Stuff), que la steel guitar de Casey Bill (Hustlin' Woman Blues) ou la mandoline de son ex-beau-frère Charlie McCoy (particulièrement brillant dans Keep On Eating, I've Been Treated Wrong ou Has Anyone Seen My Man?) colorent sa musique, celle-ci reste âpre, dramatique, chargée du poids de son histoire comme des réalités du ghetto. Et c'est en 1938, lors d'un passage à Memphis, qu'elle rencontre celui qui, l'année suivante, deviendra son dernier mari, le guitariste Ernest Lawlars dit Little Son Joe, né dans l'Arkansas le 18 mai 1900 et actif sur la scène locale (il a joué et enregistré avec Robert Wilkins et participe aux activités de plusieurs jug bands). Un nouveau duo de guitares se forme et enregistre à Chicago en 1939. Son Joe est d'ailleurs invité à "pousser le couplet" sur quelques compositions personnelles dont Diggin' My Potatoes qui deviendra un énorme succès après être passé par les doigts de Washboard Sam puis par ceux de Memphis Slim (cf. EPM/Blues Collection 158662 et 158032). Il s'agit donc ici de la version originale, une rareté que nous devons à Etienne Peltier. Mais bien vite, Little Son Joe va se mettre totalement au service de son épouse, devenant même "Mr Memphis Minnie" sur une face de disque ! Toutefois, quelques signes d'essoufflement apparaissent après la guerre et la grève des studios. Malgré une forme d'expression restée très brute, très directe et peu marquée par les maniérismes du blues urbain d'avant-guerre, Memphis Minnie va devoir, elle aussi, "céder la place aux jeunes". Peut-être plus à cause de son âge, 50 ans, que de sa musique qui, électrifiée, passe encore très bien la rampe. Au tournant des années 40/50, elle vit et travaille plusieurs années à Detroit, tourne dans le Sud où elle triomphe encore au Palace Club de Memphis en 1947, puis toujours avec Son Joe, tente de défendre sa place dans les clubs de la Cité des Vents. Puis, souffrant de crises d'asthme de plus en plus aigües, elle regagne pourde bon Memphis en 1957. Le couple se produit encore occasionnellement mais Joe, malade également, meurt le 14 novembre 1961. Minnie, paralysée et oubliée de tous ou presque — le critique belge Georges Adins lui rend visite en 1962 —, séjournera une dizaine d'années en hospice avant de finir ses jours chez sa sœur cadette le 6 août 1973, à peu près au moment même où ses disques commencent à être réévalués par les amateurs qui la placent désormais au tout premier rang des chanteuses de blues traditionnel. S'exprimant dans un idiome totalement différent de celui des Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith et autres grandes chanteuses du blues classique, Memphis Minnie a été la première femme à réellement faire sortir le blues rural de son terreau et le lancer avec aplomb et succès sur une scène où les hommes étaient rois. Malgré ou grâce à une voix non travaillée et un peu monocorde, parfois criarde mais pleine, forte, persuasive et qui interpelle, elle s'est taillé une place dans ce monde dominé par la gent masculine, Memphis Minnie est demeurée, avec son "admirable jeu de guitare, aux notes précises et cinglantes sur un rythme impeccable", dixit Gérard Herzhaft, la plus pure représentante du blues authentique vu sous l'angle de la femme. Elle en est devenue l'archétype et n'a jamais vraiment été remplacée. Dans son genre, elle fût la plus grande. Jean Buzelin

Within a puritanical and patriarchal American society, hidebound by moral, religious, social and family (not to mention money) values, black women were the last to reap any benefit from emancipation. While the beloved black “Mammy” of so many rich white families and the black woman pastor, revered by her flock, might lay claim to a certain autonomy — even authority — it was difficult for most black women to assume a role other than that of wife and mother. There was one means of escape — that offered by the world of show business. But this was also a harsh and cruel milieu where a blues prima donna, whether classical or vaudeville, might be flaunting her rhinestone jewels and feather boa one minute and the next find herself on the pavement with the rest of the bums washed up by the Depression. And so the blues came back to their old haunts — dark alleyways, dingy bars, small seedy clubs, a world of violence and poverty. And it was here that a tough, gutsy, sharp-tongued little woman grew up, nicknamed Memphis Minnie by an imaginative producer in 1929, after Walt Disney’s mouse! Born Lizzie Douglas on 3 June 1897 in Algiers on the outskirts of New Orleans, when she was seven she and the rest of her family (numbering thirteen kids) moved to Walls, Mississippi. She first learned to play banjo and then guitar and, by 1908, was already appearing at local parties, under the name of “Kid Douglas”. An unruly and impetuous child, she ran away from home in 1910 at the age of 13 and made her way up to Memphis to try to carve out a corner for herself in the cut-throat jungle that was Beale Street at that time. After playing on the streets and in Handy Park she joined the Ringling Brothers Circus in Clarksdale, Mississippi in 1916 and she toured the South with this tent show until 1920.Back in Memphis, Lizzie worked the bars and streets while living with Will Weldon, guitarist with the Memphis Jug Band, as his common-law wife. And then, in 1929, she met and legally married Joe McCoy, who also played guitar but with the Beale Street Jug Band. That same year the couple, calling themselves “Kansas Joe and Memphis Minnie”, made their first records in Memphis, including Bumble Bee, a title that was destined to become a hit far beyond the confines of the South. The couple soon moved to Chicago where, from 1930 onwards, they produced a prolific number of records and appeared at all the best spots in town. However, by 1935 McCoy had become increasingly jealous of his wife’s success as she outshone him on stage more and more, and they finally went their separate ways. There is no doubt that Memphis Minnie (who still continued to sign her works under the name of Minnie McCoy) had what it takes to embark on a solo career. She was now 38 years old and the next ten years were to see her reputation grow along with the development of urban blues in Chicago in which she played a major role. It is this period that we have chosen to illustrate with this CD, on which Minnie plays with typical Chicago Blues formations frequently featuring the pianist, Black Bob, with whom she appeared at the Tavern Hotel in 1936 (He’s In The Ring, dedicated to the most popular Afro-American figure of the time, boxer Joe Louis, If You See My Rooster …). But she also recorded some extremely beautiful solo guitar titles (Down In New Orleans, Hoodoo Lady …), rarely venturing outside the blues idiom. While the trumpet of Alfred Bell may fill out the group (Hot Stuff) and Casey Bill’s steel guitar (Hustlin’ WomanBlues) or the mandolin playing of her one-time brother-in-law, Charlie McCoy (particularly outstanding on Keep On Eating, I’ve Been Treated Wrong or Has Anyone Seen My Man?) colours her music, this still remains bitter and dramatic, reflecting as much her own story as the harsh realities of the ghetto. In 1938, on a return trip to Memphis, she met the man who was to become her last husband, guitarist Ernest Lawlars, known as Little Son Joe, born in Arkansas on 18 May 1900 and well-known locally (he played and recorded with Robert Wilkins and sat in on several jug bands). The new guitar duo they formed recorded in Chicago in 1939 where “Son Joe” was also invited to play some of his own compositions, including Diggin’ My Potatoes” which became an enormous success after versions by Washboard Sam and Memphis Slim (cf. EPM/Blues Collection 158662 and 158032). Here we have the original version, a rarity that we owe to Etienne Peltier. But very soon Little Son Joe was to become merely his wife’s shadow … he even appears as “Mr. Memphis Minnie” on one track! In addition to the delicate guitar accompaniment he provided he also wrote several tunes for her, including Me And My Chauffeur and I‘m So Glad, forever linked with her name. A new era now began for Memphis Minnie whose popularity within the black community continued to increase: numerous recordings which were continually played on juke-boxes, regular appearances at the top blues clubs in town, including Gatewood’s Tavern where her Blue Monday parties were famous. However, in the period after the war and the recording strike she was already showing some signs of breathlessness due to asthma. In spite of a style of singing that never lost its original toughness and directness and showed little of the influence of pre-war urban blues, Memphis Minnie was having to make way for younger artists. Perhaps more due to the fact that she was now 50 years old rather than to her type of music which was still very popular. During the late 40s and early 50s she lived and worked for several years in Detroit, toured the South, where she made she made another triumphal appearance at the Palace Club in Memphis before, still with Son Joe, she attempted to make a come-back in the clubs in Windy City. Then, her asthma attacks becoming more and more acute, she returned to Memphis for good in 1957. The couple continued to make the odd appearance but Joe, ill himself, died on 14 November 1961. A now paralysed Minnie, forgotten by almost everyone — the Belgian critic Georges Adins did visit her in 1962 — spent ten years in a home before dying at her younger sister’s in August 1973, just at the time her records were being rediscovered and reassessed by fans who now regarded her as one of the finest female traditional blues singers. Expressing herself in an idiom that was totally different from that of Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith and other great classical blues singers, Memphis Minnie was the first woman to have the audacity to take rural blues out of their birthplace and launch them successfully in a hitherto male-dominated milieu. In spite of, or because of, her untrained and somewhat monotonous voice, occasionally shrill but rounded, strong, persuasive and arresting, she carved out a place for herself in this men’s world which, led by Big Bill Broonzy, admitted admiringly that “she played guitar like man” and drank as much whisky! While other female singers, such as Georgia White or Lil Green, may have been more successful in the 30s and 40s because they “jazzed up” their music, Memphis Minnie’s “formidable guitar technique, with its precise, driving notes and faultless rhythm” to quote Gérard Herzhaft, makes her the most outstanding female exponent of pure, authentic blues. A position she has never really lost.