Votre panier

Il n'y a plus d'articles dans votre panier

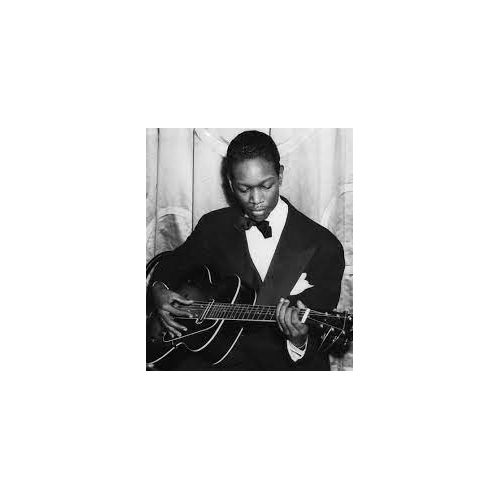

CHARLIE CHRISTIAN BENNY GOODMAN SEXTET

R313

8,00 €

TTC

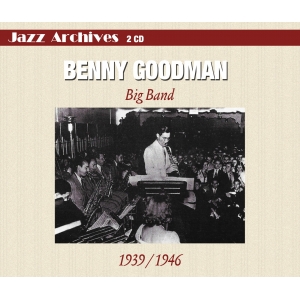

1 CD - 18 TITRES / CHARLIE CHRISTIAN / 1939-1941 / Benny GOODMAN sextet with Charlie CHRISTIAN / JAZZ ARCHIVES

VOUS RECEVREZ UN BON D'ACHAT 10% À PARTIR DE 40 € DE COMMANDE

POUR REGARDER, PARTAGER LES VIDÉOS CLIQUEZ SUR LE BOUTON "VIDÉOS" CI-DESSUS

CHARLIE CHRISTIAN / BENNY GOODMAN SEXTET

1 - Flying home.

2 - Rose room.

3 - Seven come eleven.

4 - Shivers.

5 - Till Tom special.

6 - Gone with that wind.

7 - The sheik of Araby.

8 - I surrender dear.

9 - Six appeal

10 - Wholly cats

11 - Royal Garden blues.

12 - Benny's bugle.

13 - Breakfast feud

14 - I found a new baby.

15 - On the Alamo.

16 - Gone with that draft

17 - A smo-o-o-oth one

18 - Air mail special

Vous pouvez écouter des extraits en cliquant sur le titre désiré au centre du player, vous avez aussi la possibilité de télécharger des titres ou l’album entier en cliquant sur les liens en-dessous de la pochette : par exemple sur iTunes ou amazon

CHARLIE CHRISTIAN / BENNY GOODMAN SEXTET

1 - Flying home.

2 - Rose room.

3 - Seven come eleven.

4 - Shivers.

5 - Till Tom special.

6 - Gone with that wind.

7 - The sheik of Araby.

8 - I surrender dear.

9 - Six appeal

10 - Wholly cats

11 - Royal Garden blues.

12 - Benny's bugle.

13 - Breakfast feud

14 - I found a new baby.

15 - On the Alamo.

16 - Gone with that draft

17 - A smo-o-o-oth one

18 - Air mail special

Les enregistrements

Charlie Christian & The Benny Goodman sextet

1-2-3 : Benny Goodman (cl), Fletcher Henderson (p), Charlie Christian (g), Artie Bernstein (b), Nick Fatool (dm), Lionel Hampton (vib) 1939

4 : Same but Johnny Guarnieri (p)

5-6-7-8 : Same but Count Basie (p) 1940

9 : Same but Dudley Brooks (p) 1940

10-12 : Cootie Williams (tp), Benny Goodman (cl), Georgie Auld (ts), Count Basie (p), Charlie Christian (g), Artie Bernstein (b), Harry Jaeger (dm) 1940

13-16 : Same but Jo Jones (dm) 1941

17-18 : Same but Johnny Guarnieri (p), Dave Touch(dm)

Vous pouvez écouter des extraits en cliquant sur le titre désiré au centre du player, vous avez aussi la possibilité de télécharger des titres ou l’album entier en cliquant sur les liens en-dessous de la pochette : par exemple sur iTunes ou amazon

Il faut essayer de s’imaginer ce que représenta l’arrivée de Charlie Christian sur la grande scène du jazz. Il n’y entra pas par la grande porte et avant de devenir une grande vedette aux côtés de Benny Goodman, il connut les honneurs, plus modestes, de la scène d’Oklahoma City ; cette ville était une plate-forme pour le jazz du South West, le blues y était également fort bien représenté.

On suppose, assez logiquement, qu’outre les dieux de la guitare blues, Lonnie Johnson en tête, Charlie Christian écouta Eddie Lang ; il était difficile de faire autrement à l’époque, puisque Salvatore Massaro (tel était son véritable nom) fut un des premiers grands guitaristes de jazz américains. Quant à savoir si Christian connut dès le milieu des années 30 la musique de Django Reinhardt, les avis divergent. D’aucuns avancent qu’à l’époque où il entra chez Benny Goodman, donc au début des années 40, il connaissait des solos de Django par cœur ; nous nous bornerons à constater que l’influence du génial manouche paraît fort accessoire par rapport à ce que l’on connaît du jeu de Christian.

A l’inverse, il serait plus intéressant d’avancer que le style de Christian semble un véritable produit des années 30 et que la révolution qu’il déclencha dans le monde des guitaristes jazz doit beaucoup à son utilisation de la guitare amplifiée (bien qu’il ne fût pas le premier à l’utiliser dans le jazz) et au fait qu’il se référa au phrasé du saxophone (et notamment à celui du ténor), allant dans le sens de la mutation parkérienne. Christian fut davantage un des derniers grands classiques que le premier bopper, et nous n’essayons pas de dire que le verre est à moitié vide plutôt que moitié plein, simplement que son travail harmonique n’était pas aussi novateur que celui d’autres géants de son temps, pas forcément des plus jeunes (Coleman Hawkins, Art Tatum). En tout cas, il libéra la guitare de son rôle d’auxiliaire (enfoui dans la masse orchestrale) et à sa suite s’engouffra toute une génération de musiciens qui fut en majorité associée au be-bop.

L’association entre Charlie Christian et Benny Goodman, le Roi du Swing eut quelque chose d’explosif. John Hammond, qui venait de le “découvrir” à Oklahoma City, n’eut de cesse que de présenter le jeune guitariste au grand clarinettiste. La suite est digne de la légende et évidement il existe deux versions de la rencontre. Selon la première, sans demander l’avis de Goodman, Christian avait été installé sur scène, muni de sa guitare et de son ampli. Goodman ne fut pas ravi de découvrir la présence de cet inconnu, il attaqua pourtant Rose Room et leur interprétation dura quarante-huit minutes. Cette version a le mérite de la fulgurance. En réalité, Goodman avait déjà entendu Christian et l’avait auditionné d’une oreille distraite, tellement distraite qu’Hammond et quelques musiciens de Goodman estimèrent que le guitariste devait avoir droit à une seconde chance.

A l’époque, Goodman était particulièrement réceptif, la Swing Era touchait à sa fin et il flottait dans l’air musical un parfum de liberté. Goodman appréciait tout particulièrement de pouvoir jouer avec des petites formations, formule beaucoup plus souple que les grands orchestres, dont l’imposant volume sonore nuit à la diversité. Avec Christian, Goodman avait l’avantage de disposer de puissance, la guitare devenant une véritable rampe de lancement, mais il pouvait pareillement compter sur le soliste : intarissable improvisateur, Christian ne ratait jamais l’occasion de se lancer dans une suite de chorus échevelés, entraînant tout l’orchestre dans son sillage.

Malheureusement, l’histoire commune du guitariste et du clarinettiste, commencée en 1939 s’acheva en 1942 par la mort de Christian. La tuberculose avait eu raison de son grand corps, il n’avait pourtant qu’un peu plus de vingt ans (il était né en 1916 ou en 1919, selon les sources).

François Billard

Just what did Charlie Christian’s arrival on the jazz scene mean? He more or less came in from the side-lines and, before sharing star billing with Benny Goodman, had been modestly successful in Oklahoma City, a centre not only of South West jazz but also of the blues.

Apart from guitar blues greats, not least Lonnie Johnson, Charlie Christian must have heard Eddie Lang (whose real name was Salvatore Massaro), one of the first great American jazz guitarists. However, opinions vary as to whether Christian was familiar with the music of Django Reinhardt in the mid-30s. Some believe that, when he joined up with Benny Goodman in the 40s, he already knew most of Django’s solos by heart. We would merely point out that the latter’s influence appears very slight from what we know of Christian’s style of playing.

On the other hand, it is much more interesting to see this style as one born out of the 30s. While he may not have been the first to amplify his guitar, his use of this instrument revolutionised the guitar’s position in jazz, as did his inventive phrasing, based on that of the sax—the tenor in particular—and his development of a new idiom along Parker lines.

Christian should be seen more as one of the last great classic jazz artists, rather than the first bopper, his harmonic ideas being somewhat less innovative than those of some of his leading contemporaries, not only the younger ones either (Coleman Hawkins, Art Tatum). But he certainly freed the guitar from its subsidiary role, often hidden away somewhere within the ensemble, thus engendering a whole new generation of jazz guitarists, mainly associated with bebop.

The Charlie Christian/Benny Goodman partnership created a veritable explosion in the jazz world. John Hammond, having just “discovered” Christian in Oklahoma City, could not wait to introduce the young guitarist to the “King of Swing”. There are two versions as to what exactly happened at this legendary encounter. One story has it that, without telling Goodman, they sneaked Christian up on to the stage, complete with guitar and amplifier. Although Goodman was less than delighted to discover this unknown musician already installed, he swung into Rose Room , their ensuing and brilliantly dazzling interpretation going on for forty-five minutes. The truth was that Goodman had already auditioned Christian but had listened to him with only half an ear. In fact, he had paid him so little attention that Hammond and the rest of Goodman’s musicians decided the guitarist deserved a second chance.

It was a time when Goodman was particularly receptive, the Swing Era was drawing to a close and there was a taste of freedom in the air. Goodman particularly enjoyed playing with small groups that offered far more flexibility than big bands, where volume tends to restrict diversity. In Christian, Goodman not only had the advantage of power, the guitar providing a forceful thrust, but he could also rely on the soloist: a tireless improviser, Christian seized on any chance to launch into a series of frenzied choruses, driving the band along in his wake.

Sadly, the partnership between the guitarist and clarinettist, begun in 1939, ended abruptly in 1942 with the death of Christian from tuberculosis. He was still only in his early twenties—sources giving the year of his birth as 1916 or 1919.

Adapted from the French by Joyce Waterhouse