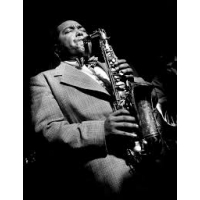

A l'automne 1947, Charlie Parker avait regagné New York, l'odyssée californienne n'avait pas été de tout repos et le séjour à l'hôpital d'Etat de Camarillo l'aboutissement provisoire d'une errance existentielle dont nous ne pouvons approcher que le versant musical. La Californie ne se trouvait pas seulement sur "l'autre côte", par rapport à New York, elle ne vivait pas au même régime, climatique et jazzistique. À Los Angeles, par exemple, la grande métropole de la Côte Ouest, le jazz demeurait isolé dans un ghetto, pas nécessairement un ghetto pour pauvres, mais il demeurait le fait d'une élite et limité à quelques clubs. Les jazzmen y étaient moins nombreux, surtout si l'on se réfère au nouveau courant, au bebop qui n'avait cessé de secouer les esprits. En somme, Parker y aurait pu vivre une semi-retraite, pratiquer sa musique avec une certaine sérénité dans des conditions matérielles fort acceptables. À New York, il retrouva la fièvre, la multiplication des petits clubs, la horde des jeunes boppers et aussi, peut-être surtout, le dynamisme de la mode. New York demeurait le parangon des modes et même si elle n'avait pas toujours le monopole de la créativité, ainsi que l'on pourrait le vérifier dans maints domaines, elle était la vitrine où s'exposèrent de tout temps les avant-gardes. À New York, donc, Parker découvrit aussi de nouveaux clubs de jazz, poussés comme des champignons, pas seulement des caves à peine améliorées mais aussi des établissements luxueux qui accueillaient la nouvelle musique. Le snobisme était omniprésent et le "jaaaz" attirait sinon des foules du moins des cohortes d'"initiés" qui se pressaient pour écouter le bebop. Gillespie qui avait vraiment su gérer sa carrière et sa réputation représentait l'extravagant prophète de la nouvelle musique. Et une musique aussi complexe que le bebop avait besoin d'une bonne dose d'images et de l'aura du mythe pour conquérir les cœurs. Parker en raison de sa longue absence et son quasi-exil en la lointaine Californie, moins médiatique que Gillespie, faisait figure de revenant, mais ses multiples intempérances donnait à son génie l'éclat trouble du scandale. Il vivait alors avec Doris Sydnor dans un hôtel de la 117e Rue et s'était vu offrir un contrat régulier au Three Deuces, l'occasion de monter un groupe régulier. Il lui fut facile de choisir ses musiciens. Miles Davis, le jeune trompettiste qu'il connaissait bien et dont l'art avait encore mûri, avait repris ses études à la Juilliard. Le choix du pianiste était moins évident, mais Parker avait trouvé en Duke Jordan, avec qui il avait souvent travaillé en 1946, une sorte de gage de stabilité car son style d'accompagnement était au service de la musique de Parker, bien qu'il ne fût pas "l'homme" de Miles Davis qui lui aurait préféré John Lewis. Max Roach, "le" batteur du bebop, et Tommy Potter, un des bassistes les plus sollicités, souvent associé à Roach, complétaient la rythmique. Cet orchestre offrait à Parker la possibilité d'explorer nuit après nuit toutes les ressources de son nouveau langage et si l'on a trop souvent exalté les vertus de la jam session, force est de reconnaître que de l'aléatoire surgit rarement la véritable innovation. Les séances d'octobre et de novembre 1947, toutes deux pour Dial, témoignent d'une sérénité et d'un plaisir de jouer ensemble, on y trouve des originaux pris sur tempo rapide, Bird Feathers, Scrapple From the Apple et Klactoveesedstene et des grands classiques de la ballade, My Old Flame, Out of Nowhere (deux interprétations magnifiques) et Don't Blame Me. Klactoveesedtene comporte un stupéfiant solo dont le périlleux découpage se résoud en une construction supérieure. Ross Russell, directeur des disques Dial, expliqua que Parker avait écrit ce titre "un soir au Deuces derrière une addition, sans plus d'explication sur son sens. quand je le lui demandai, il me jetta un regard froid et tourna les talons. S'agissait-il de quelqu'un, d'un lieu, d'une idée abstraite ou d'un nouveau terme du lexique jive ? Après avoir consulté le gros Webster, puis le dictionnaire étymologique de Skeat sans plus de résultat, je m'adressai à Dean Benedetti : "Klactoveesedsteene ? Des sons, c'est tout mon vieux !" Quant à Scrapple from the Apple, il mérite aussi de capter l'attention, qui fit écrire à André Hodeir que "ses harmonies de passage (...) sont les fruits d'une imagination mélodique, aussi délicatement inventive" que celle du Benny Carter de Hot Mallets et de When Lights Are Low.

En cette fin d'année1947, sous la tutelle du critique Barry Ulanov, fut réuni une sorte de who's who du bebop, des musiciens venus d'horizons différents. Le résultat dépassa très largement les fulgurances d'une jam session. Il y eut deux rencontres, la première eut lieu les 13 et 20 septembre 1947, outre Parker, l'orchestre était formé de Dizzy Gillespie à la trompette, de John LaPorta à la clarinette, de Lennie Tristano au piano, de Billy Bauer à la guitare, de Ray Brown à la contrebasse et de Max Roach à la batterie (de cette rythmique, Alain Tercinet écrivit justement qu'elle "préfigure les prises de position libertaires qui deviendront monnaie courante dans le free jazz" (in Be-bop, Ed. P.O.L, Paris, 1991). Le prétexte avait été une bataille d'orchestres expliqua Barry Ulanov : "un orchestre moderne était en compétition avec une formation Nouvelle-Orléans ... Nous avons fait deux émissions... les auditeurs votaient par carte postale pour leur formation préférée." L'intérêt de cet affrontement est qu'il réunissait dans le cas des modernes des hommes que l'on ne se serait pas forcément attendu à voir jouer ensemble, une phalange tristanienne — outre le pianiste, Billy Bauer à la guitare et John LaPorta à la clarinette — et quelques caïds du bop. Quelques mois plus tard, Barry Ulanov réunit, sous le drapeau des All Star Metronome Jazzmen un orchestre assez similaire, auquel s'était ajouté le ténor de Allen Eager; Fats Navarro, Tommy Potter et Buddy Rich ayant respectivement remplacé Gillespie, Brown et Roach. Nous avons retenu deux morceaux de cette dernière séance (deux fameuses composition de Parker, Koko et Donna Lee), Charlie Parker s'y montre particulièrement à l'aise et l'approche tristanienne qui caractérise la rythmique s'avère extrêmement stimulante, ce qui ne devrait étonner personne puisque Parker et Tristano aimaient à se retrouver pour improviser tous deux dans le studio de Lennie à Manhattan. Pas de jazz coupé en deux, pas de cool school ou de bebop blanc opposé au bop parkérien, une formidable complémentarité, un contexte étonnamement fécond pour le bebop !

À New York, l'orchestre régulier de Charlie Parker continua à enregistrer pour Dial et le17 décembre 1947, J.J Johnson (particulièrement en valeur sur Crazeology), le grand tromboniste du bebop s'était joint au petit orchestre. Parker venait de s'autoriser une petite escapade et s'était rendu à Detroit avec son quintette pour y jouer deux semaines. Le séjour fut plutôt houleux, l'héroïne s'en était mêlé, ce qui pourrait expliquer, selon Ross Russell, le climat de cette séance, comme l'ombre d'une certaine fatigue, une sorte d'usure qui affectait imperceptiblement la musique sans toutefois lui ôter de sa qualité.

Le 21 décembre, Parker retrouva les studios Savoy, cette fois sans J.J. Johnson. La séance eut lieu à Detroit, Bird étrennait un saxophone Selmer flambant neuf et toutes les compositions, inédites, étaient nées de sa plume. Des blues, bien entendu et deux dérivations de standards, Klaustance, issue (mais si lointainement) de The Way You Look Tonight et Bird Gets the Worm sortie de Lover Come Back to Me. Dans Bird Gets the Worm, remarquons les 4/4 entre la batterie de Max Roach et la contrebasse de Tommy Potter, une formule apparemment inédite. En ces derniers mois de 1947, la musique de Parker, appréciée jusqu'alors par les initiés, commençait à toucher un public plus large, l'avenir s'annonçait plus clément, mais le ciel demeurait nuageux.

François Billard

In the autumn of 1947, Charlie Parker regained New York after a Californian odyssey that had hardly been restful and a stay in Camarillo state hospital—the result of a way of life that we can only approach through his music. Not only was California on the opposite coast from New York, with a different climate, but its jazz climate was not the same either. In Los Angeles on the West Coast, for example, jazz remained isolated within a ghetto, not necessarily a poor ghetto, but it was the music of a chosen elite and limited to a few clubs. There were fewer jazzmen around, especially in the new domain of bebop. In fact, Parker could have had an easy life there, working part-time and making a comfortable living from his music. In New York, on the other hand, he found himself back in the feverish atmosphere of numerous small clubs, crammed with teenage boppers and, above all, tributary to the dictates of musical fashion. New York represented everything that was new and, even though it may not have had a monopoly on creativity (as is obvious in several areas), it remained the showcase of avant-gardism. On his return to New York, Charlie Parker discovered a whole lot of new jazz clubs that had mushroomed overnight, not only in scruffy basements but also in luxurious venues that welcomed the new music. A certain form of intellectual snobbery was evident and jazz attracted crowds of so-called “initiates” who flocked to listen to bebop. Gillespie, who had managed his career and reputation very cleverly, was seen as the extravagant prophet of this new music. In order to conquer the masses, music as complicated as bebop really needed outstanding figures and a certain mystic aura. Because of his long absence and virtual exile in California and less in the public eye than Gillespie, Parker appeared as someone who had returned from the dead but his excesses gave rise to all kinds of scandal. He was living at the time with Doris Syndor in a hotel on 117th Street and was offered a contract at the Three Deuces that enabled him to set up his own group. He had no problem in choosing his musicians. He knew the young Miles Davis who had become an accomplished trumpeter and had taken up his studies again at the Juillard. However, finding a pianist was not quite so easy but in Duke Jordan, with whom he had often worked in 1946, Parker found a reassuring backing for his style of accompaniment suited Parker’s music, although it was not always to the taste of Davis who would have preferred John Lewis. Max Roach, the bebop drummer, and bassist Tommy Porter who was used to playing alongside Roach completed the rhythm section. Appearing nightly with this formation gave Parker the opportunity to explore all the possibilities of his new musical language for, while jam sessions have often been exalted as a source of inspiration, such chance encounters rarely gave rise to true innovation. The two Dial sessions from October and November 1947 reveal how much the group enjoyed playing together on up-tempo versions of Bird Feathers, Scrapple From The Apple and Klactoveesedstene, on the great ballad classics My Old Flame, Out Of Nowhere (two magnificent interpretations) and Don’t Blame Me. Klactoveesedstene features a stupefying Parker solo, his patchwork phrasing resulting in an overall subtly varied pattern. Dial’s manager Ross Russell, explains that this title was Parker’s own: “He wrote it out one night at the Deuces on the back of a minimum charge card, offering no explanation of its meaning. When I asked, he gave me a stony stare and walked off. Was it a person, a place, an abstract idea, or a new entry in the jive lexicon? After consulting the large desk model of Webster’s and after that Skeat’s Etymological Dictionary, both without result, I asked a psychiatrist if she could help. She could not. Then I consulted Dean Benedetti, who pointed out at once what was to him quite obvious: “Klactoveesedstene? Why, man, it’s just a sound.” (1). According to André Hodeir, Scrapple From The Apple also merits attention for “its harmonic passages (…) are the fruit of a melodic imagination, that is as inventive” as that of Benny Carter on Hot Mallets and When Lights Are Low.

Towards the end of 1947, jazz critic Barry Ulanov arranged the get-together of a sort of bebop “Who’s Who” that included a variety of musicians. The results far exceeded those of the short-lived brilliance of a jam session. The first of these meetings took place on 13 and 20 September 1947. Besides Parker, the orchestra comprised Dizzy Gillespie on trumpet, John LaPorta on clarinet, Lennie Tristano on piano, Billy Bauer on guitar, Ray Brown on bass and Max Roach on drums. (In Bebop, Ed. P.O.L., Paris, 1991, Alain Tercinet wrote that this line-up foreshadowed the freedom of expression that would become the hallmark of free jazz). Barry Ulanov explained that the pretext was “a “Battle of the Bands”, broadcast on the Mutual Network. It was a modern group versus a New Orleans combination… It was just a couple of broadcasts…The listeners chose the modern group in a postcard balloting.”(2) The interest lies in the fact that the modern group included musicians that one would not necessarily have expected to find playing together: a Tristano cohort—in addition to the pianist, Billy Bauer on guitar and John LaPorta on clarinet—plus some bop stalwarts. A few months later, under the name of the All Star Metronome, Barry Ulanov reunited a fairly similar band, with the addition of tenor Allen Eager. Fats Navarro, Tommy Potter and Buddy Rich replaced respectively Gillespie, Brown and Roach. We have included here Koko and Donna Lee from this later session, both well-known Parker compositions on which he appears particularly at ease, the Tristano-led rhythm section providing a particularly stimulating backing. This is hardly surprising since Parker and Tristano often met up to improvise in Lennie’s Manhattan studio. Here there is no split between cool jazz and bebop à la Parker, simply an extraordinary complementarity, an extremely fertile context for bebop!

In New York, Charlie Parker’s regular formation continued to record for Dial and on 17 December 1947, the great bebop trombonist J.J. Johnson (outstanding on Crazeology) joined the group. Parker had just been to Detroit with his quintet to play a two-week stint. The trip had been a stormy one in which heroin played a large part which, according to Russ Russell, explains the atmosphere at this session, one of fatigue, but Parker’s perfunctory playing did not detract from the overall quality.

On 21 December Parker was back in the Savoy studios in Detroit, this time without J.J. Johnson. Bird was trying out a brand new Selmer sax and all the compositions came from his pen. Blues, of course, and two reprises of standards: Klaustance, based (somewhat vaguely) on The Way You Look Tonight and Bird Gets The Worm derived from Lover Come Back To Me. Note on Bird gets The Worm the 4/4 between Max Roach’s drums and Tommy Potter’s bass, something apparently not done before. By the end of 1947, Parker’s music, hitherto appreciated only by initiates, began to reach a wider audience. The future looked promising but storm clouds were still hovering around.

Adapted from the French by Joyce Waterhouse

Notes:

(1) Bird Lives, The high life and hard times of Charlie “Yardbird” Parker by Russ Russell (Quartet Books, London 1980).

(2) Bird: The Legend of Charlie Parker by Robert Reisner (Quartet Books, London 1962).