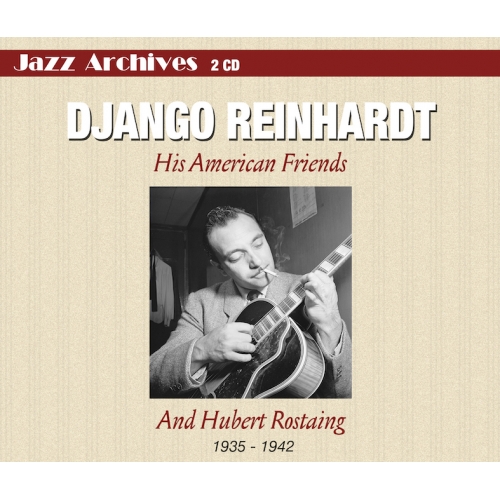

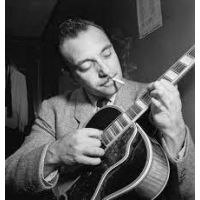

C'est en Belgique qu'est né Django (Jean) Reinhardt. La chose arriva le 23 janvier 1910 à Liberchies, près de Charleroi (Province du Hainaut). Et l'acte de naissance précise que pour l'officier de l'Etat Civil, le nom de la famille s'écrit "Reinhart" (sans "d"), tandis que la dite famille préfère signer au bas du document "Reinhard" (sans "t"!)... Mais, on le sait, l'orthographe ne fut jamais la préocupation principale de ces fous de liberté qui aimaient bien mieux se balader en verdine. Plus tard, quand le jeune banjoïste fera ses premières armes dans les studios auprès d'accordéonistes en renon (1928), les gens des maisons de disques, incapables de comprendre son nom ou de le lui faire écrire, indiqueront approximativement sur les étiquettes "Iango Renard" et même "Jean Got" (sic!). En 1934-35 encore, il n'est pas rare de voir orthographier son prénon "Jungo". En plus il semble qu'outre ses difficultés à tracer des lettres (ou des notes !), il ait eu un petit défaut de prononciation : dans le Festival Swing 1941, il s'annonce lui-même, avec un léger cheveu sur la langue -ce qui donne à peu près "Dzungo Renard"... Après cela, allez savoir !...

Et puis, de toutes façon, "Reinhar(d)(t)", c'était le patronyme de la maman, prénommée Laurence (alias "Negros"). Danseuse et acrobate de talent follement éprise de son indépendance, elle refusa toujours de convoler en justes noces. Elle avait déjà un enfant quand naquit Django. Le papa de ce dernier (puis, deux ans après, d'un autre garçon, Joseph -alias "Ninin"- qui devint lui aussi guitariste), musicien et luthier de son état, répondait au nom de Jean Vées. Il n'est pas impossible que ce Jean-là (ou bien un de ses proches parents) ait aussi enfanté ailleurs, puisqu'un troisième larron de la guitare tzigane, appartenant à la génération de Django et Joseph, s'appelle Eugène Vées (alias "Ninine")...

En fait, ce n'est pas tout-à-fait un hasard si Django et Joseph Reinhardt sont nés en Belgique. Les Tziganes sont des nomades, certes, mais ils ont, selon les groupes, leurs territoires de prédilection. Ainsi, si l'on trouve principalement la branche des Gitans dans le sud de la France, en Espagne, au Portugal et en Italie, la branche des Manouches (dont Django et son frère sont des représentants) se rencontre surtout, elle, en Belgique, en Hollande, en Allemagne et dans le nord de la France. Donc...Ce qui ne veut évidement pas dire que, de temps en temps, les Gitans ne vont pas se promener dans le Nord, ni les Manouches dans le Sud ! Par exemple, au moment où éclate la première guerre mondiale, toute la bande se trouve du côté de Nice, puis passe en Italie, s'embarque pour la Corse et finit par échouer en Afrique du Nord. Quand fut terminée cette guerre qui ne les concernait qu'assez vaguement (bien que la famille Reinhardt eût préféré, en 1871, quitter Strasbourg devenue allemande), on revint vers Paris et on installa la roulotte sur la zone, près de la barrière de Choisy. Django vécut là pendant près de quinze ans, courant les rues de Paris, évitant soigneusement d'apprendre à lire et à écrire, jouant du banjo dans les bals-musette auprès des caïds du piano-à-bretelles, rêvant peut-être de revoir ce Nord rude et mystérieux qui l'avait vu naître et qu'il ne connaissait pas...

Le Nord, la Belgique, il put y séjourner parfois, dans la seconde moitié des années trente, quand, en compagnie de Stéphane Grappelli, il était devenu le principal soliste du fabuleux Quintette du Hot Club de France, fondé en 1934. Néanmoins, il n'eut pas à l'époque l'occasion d'y enregistrer. L'occasion, elle ne vint, paradoxalement, que quelques années plus tard, en 1942, durant les jours douloureux de l'Occupation allemande. Lors de la déclaration de guerre, début septembre 1939, le quintette à corde se produisait en Angleterre. A l'annonce de l'ouverture des hostilités, Django, les deux autres guitaristes, le bassiste, reprirent le chemin du pays. Seul Grappelli préféra rester là-bas. Pour le remplacer, Django imagina un "nouveau" quintette où la clarinette remplacerait le violon : un violoniste de la classe de Stéphane était à peu près impossible à trouver, tandis qu'un clarinettiste... On lui présenta le jeune Hubert Rostaing, qui préférait le saxophone mais pratiquait l'instrument, était originaire de Lyon et avait passé son enfance en Algérie. La rencontre eut lieu à la fin de la "drôle de guerre", mais l'association ne se concrétisa qu'au retour de la débâcle. Dès lors, le nouveau Quintette devint une grande vedette populaire, alors que l'ancien n'avait fait la joie que de quelques "happy few"... Mais sa carrière internationale se trouvait interrompue pour un bon bout de temps !

Pourtant, malgré l'envahissement de l'Union Sovietique au printemps 41, malgré l'attaque japonnaise à l'endroit des USA (où Django avait depuis longtemps une jolie cote) à la fin de la même années, en Europe occupée les relations entre différents pays sous la botte commencèrent à se "normaliser". Notamment avec la Belgique, la plus proche voisine, où vinrent jouer, dès le printemps 42, Charles Trenet accompagné par son pianiste Léo Chauliac, ainsi que le Quintette. Un peu plus tard, à l'été, ce fut le tour d'Alix Combelle et de son "Jazz de Paris" (qui, eux aussi, firent quelques disques). En 1943, les Belges eurent droit à Gus Viseur, le Roi de l'accordéon "swing" (encore un enfant du pays), ainsi qu'à ce jeune pianiste nommé Eddie Barclay...

En contrepartie, la France accueillit la grande formation bruxelloise du saxophoniste Fud Candrix, vieil habitué des salles parisiennes avant la guerre. Lui rendant sa politesse de l'année précédente, Django l'invita à l'accompagner dans quelques faces. A Bruxelles en avril 42, en effet, c'est Candrix et une partie de son équipe que l'on avait réquisitionnés pour seconder Django, Rostaing et la rythmique du quintette eux-mêmes récupérés au vol (c'est le cas de le dire !) par une importante firme phonographique locale. Peu après, la même maison fit également enregistrer Trenet et Chauliac. Il fut décidé que, pour une fois, le guitariste et le clarinettiste joueraint séparément. Le premier ouvrit le feu, uniquement accompagné par le pianiste Ivon de Bie, en gravant quatre faces assez curieuses. Trois (Vous et Moi, Distraction et le très connu Studio 24) sont dûes à l'inspiration de musiciens belges, la quatrième, Blues en Mineur (fort proche, en vérité d'un certain Minor Swing de 1937) étant signée par Django lui-même. Surtout, l'on se doit de remarquer que sur ce Blues ainsi que sur Vous et Moi, non content de pincer ses cordes, Django se plait également à racler le violon. Chose qu'il faisait, dit-on, couramment avant cet accident qui, fin 1928, lui ôta l'usage de deux doigts de la main gauche. ce sont là les seuls témoignages que l'on possède de lui sur cet instrument. La sonorité, l'attaque, le révèlent encore plus farouchement tzigane qu'avec sa guitare. Dommage que le "re-recording" n'ait pas encore été inventé à l'époque ! Les morceaux suivants furent enregistrés avec la grande formation de Candrix. Place de Brouckère, composition nouvelle, hommage à un haut-lieu bruxellois aujourd'hui envahi de béton, s'imposait évidemment. Mixture est l'oeuvre du saxophoniste, quant aux deux titres restants, Seul ce Soir et le délicat Bei Dir war es immer so schön, il s'agit de deux grands tubes de la chanson germano-française (un genre très en vogue en ce temps-là !). Le même jour, Rostaing, remplaçant son chef bien aimé, grava à son tour quelques galettes supplémentaires avec un contingent du même orchestre. Cinq d'entre elles se trouvent ici reproduites pour la première fois, semble-t-il, depuis leur parution en 78 tours. Voix du Monde est, de nouveau, l'oeuvre de Candrix et de l'altiste Bobby Naret, tandis que Paulette, Adieu et Croisades portent la signature de Rostaing. On notera que, ça et là, lui aussi se plait à changer d'instrument en troquant sa clarinette contre un saxophone ténor. En fait, Django, désireux d'obtenir une sonorité d'ensemble légère, proche de celle de l'ancien quintette à cordes, lui avait carrément interdit, dès son arrivée dans le groupe, d'user des saxophones, mais cette fois, il ne pouvait rien dire !.. Il existe quelques autres faces enregistrées par Rostaing lors de ces séances d'avril et mai 42, mais l'état assez effrayant de ces originaux plutôt rares ne nous a pas permis de les inclure. Au demeurant, même quand ces disques sont neufs (chose assez peu fréquente), la pate de guerre dans lesquels ils ont été pressés est si médiocre que le bruit de surface demeure très élevé. Nous avons tenté de la limiter au maximum sans nuire à la présence et à la couleur de la musique...

Django Reinhardt raffolait des grands orchestres. Dans les années 30, il joua fréquemment dans certaines de ces grosses machines et, par la suite, tenta d'en constituer lui-même chaque fois qu'il le put. Après la guerre, il fut ravi d'être engagé par Duke Ellington. De même dut-il être particulièrement heureux d'avoir pour l'accompagner en mai 42 un véritable "jazz symphonique". Pionnier du jazz belge, Stan Brenders dirigea sans doute le grand orchestre le plus célèbre du pays pendant l'Occupation. La présence d'une importante section de cordes, loin de rendre l'ensemble sirupeux, apporte une coloration étrange, ouatée, rêveuse, aux trois premiers morceaux, Djangology (un déjà vieux succès), Begin the Beguine (grand tube d'outre-Atlantique au titre prudemment traduit en français !) et, surtout, Nuages, chef-d'oeuvre de l'art de Django compositeur, au titre de circonstances, déjà enregistré par deux fois à l'automne de 1940, année de sa création. Sans doute avons-nous ici la plus belle version. On peut regretter que les quatre morceaux suivants aient été enregistrés sans les violons, mais il est vrai que, s'apparentant à une esthétique plus traditionnelle (il y a même, avec Django Rag, une version à peine dissimulée du vieux Tiger Rag, et, avec Chez Moi à Six Heures, une chose très dans la manière de Count Basie), il en avaient moins besoin. Ce jour-là encore, Hubert Rostaing grava lui aussi quelques faces, dont Hésitation et Mohican (une façon, quelque peu détournée de se référer à l'Amérique !)...

Cette Amérique où Django ira donc enfin se faire entendre en chair et en os en 1946 et 1947. Ensuite, il préfèrera assez souvent l'Italie -ce qui ne l'empêchera tout-de-même pas de revenir de temps en temps à Bruxelles. Mais les jours lui sont comptés, puisqu'il s'éteindra brûtalement le 15 mai 1953, à l'âge de quarante-trois ans. Quinze ans plus tard, le conseil municipal de sa ville natale, Liberchies, avança l'idée d'ériger une stèle ou de batir un monument commémoratif. Mais le projet fut abandonné car, précise Charles Petit-Jean, Premier Echevin, "les fonds ont manqué"...Daniel Nevers

It was in Belgium that Django Reinhardt was born: in a little town called Liberchies, near Charleroi, on 23 January 1910. And for the registry-office official issuing the birth certificate the family name was spelled “Reinhart” (without the “d”), whereas for the members of the family who signed the document it was spelled “Reinhard” ( without the “t”). But, then, spelling never was the strong point of gypsies! Later, when the then young banjo-player was making his first studio visits as sideman in some of the top accordion bands of the day (1928), record-company executives, unable to understand his name or get him to write it, reproduced it as best they could: sometimes as far adrift as “Iango Renard” or “Jean Got”. Even as late as 1934-35, it was not rare to see his first name written “Jungo”. Moreover, Django himself, in addition to not being able to write, seems to have suffered from a slight speech impediment: on Festival Swing 1941, introducing himself with something of a lisp, he seems to say “Dzungo Renard”. So the precise name could to be anybody’s guess!

In any case, that family name of “Reinhar(d)(t)” came from Django’s mother, Laurence (alias “Negros”), a dancer and acrobat of such ferociously independent disposition that she always refused to marry. She was already the mother of one child when Django was born. Django’s father (who two years later fathered another son, Joseph, alias “Ninin”, yet one more guitarist in the making) was a musician and violin-maker by the name of Jean Vées. Now it is by no means improbable that this same Jean (or one of his close relatives) also fathered elsewhere, since a third member of this same generation of gypsy guitarists, present here, bore the name of Eugène Vées (alias “Ninine”).

The fact that Django and Joseph Reinhardt were born in Belgium was by no means the result of mere chance. The Tzigane gypsies may be nomads, but each group has its preferred territory. Hence, the Gitan branch is to be found mainly in the South of France, Spain, Portugal and Italy; whereas the Manouche branch to which Django belonged congregates mainly in the northern areas of France, Belgium, Holland or Germany. This is not, of course, a hard and fast rule: when, for example, the first world war broke out, the whole band made for Nice, then moved on to Italy, from there to Corsica, and finally into North Africa. At the end of hostilities, the northern families headed back “home”, and the Reinhardt clan parked its caravan in one of Paris’s gypsy areas at the Porte de Choisy. Which is where Django lived for the next 15 years or so: roaming the streets of Paris, carefully avoiding learning to read and write, playing banjo in the accordion bands of the popular “bals musette”, and perhaps even dreaming of visiting those mysterious northern territories where he was born, but which he had never actually seen.

He was finally able to visit Belgium in the second half of the 1930s, by which time, alongside Stéphane Grappelli, he had become star soloist of the fabulous Quintet of the Hot Club of France, founded in 1934. But he would not have the chance to record on his native territory until 1942, ironically at a time this entire region of northern Europe was firmly under the Nazi boot. When the second world war had broken out in September 1939, the famous HCF string-quintet was appearing in London. On hearing the news, Django, the two rhythm-guitarists and the bassist headed hotfoot for home, with only Grappelli preferring to stay on in London.

Once back in Paris, Django had started to dream up a new quintet in which the inimitable Grappelli violin would be replaced by a clarinet, an easier chair to fill. He was introduced to Hubert Rostaing, a native of Lyon brought up in Algeria, first and foremost a saxophonist but more than capable of doubling on clarinet. This first meeting took place during the early days of war, but the two of them did not actually get round to working together until after the fall of France. At which time this new quintet of Django’s soon found itself an immensely popular attraction, whereas its eminent predecessor had enjoyed success among little more than specialist audiences.

Despite the spread of the war into the Soviet Union in the spring of 1941, plus the involvement of the USA later that same year, life in occupied Europe was beginning to resume a certain, albeit resigned, normality. Consequently, by the spring of 1942, French artists such as Charles Trénet and his pianist Léo Chauliac, as well as Django’s quintet, were able to land engagements in nearby Belgium. By the summer, it was the turn of Alix Combelle and his “Jazz de Paris”, followed in 1943 by that king of swing accordion, Gus Viseur, and a young pianist by the name of Eddie Barclay.

France then responded by welcoming the Brussels-based big band led by saxophonist Fud Candrix, a Paris regular in prewar days. Which gave Django the opportunity to return a compliment of the year before by inviting them to record a few sides with him. Indeed, in April 1942, Fud Candrix and his outfit had been pressed into service in Brussels to accompany Django, since the large Belgian record company in charge of operations had decided to feature Hubert Rostaing, also backed by some of Candrix’s men, as a separate attraction. In both line-ups, the rump of the quintet rhythm-section (Vées, Soudieux and Jourdan) replaced their Candrix counterparts.

It was Django who opened fire, first cutting four curious sides accompanied only by band pianist Ivon De Bie. Three of these (Vous et Moi, Distraction and the well-known Studio 24) stemmed from the pens of Belgian musicians, whereas the fourth, Blues en Mineur (extremely close, in truth, to the 1937 Minor Swing), was a Django original. Doubtless of greatest significance, however, is that on this blues number, and on Vous et Moi, Django also plays violin, something he apparently often liked to do prior to the accident in 1928 that deprived him of the use of two of the fingers of his left hand. Certainly, these are the only recordings we have of him on this instrument. His tone and attack on violin reveal an artist even more ardently gypsy than on guitar, which makes us regret that re-recording techniques had not yet arrived in Europe!

The four pieces that follow were recorded in the company of Candrix’s full big band. Place de Brouckère, a new piece by Django named in honour of a renowned Brussels site today a mass of concrete, was an obvious candidate for attention. Mixture came from the pen of Candrix, whereas the two remaining pieces, Seul ce Soir and the delicate Bei Dir war es immer so schön were two current hits from the then much-in-fashion Germano-French repertoire!

At which point in the proceedings, Rostaing took over from Django and, backed by a contingent from the same orchestra, recorded a number of sides of his own. Five of those are included here, making their first reappearance, it would seem, since their initial release on 78s. Voix du Monde is a co-composition by Candrix and his alto-sax man Bobby Naret, while Paulette, Adieu and Croisades are all Rostaing originals. Taking advantage of his position as leader, Rostaing here occasionally switches to tenor-sax, something Django, keen to reproduce the light, airy sound of the original string quintet, had expressly forbidden him to do within the Hot Club of France format.

There are a few more Rostaing sides from these April and May 1942 Brussels sessions, but the dreadful condition of the rare originals has prevented us from including them. Indeed, even when we can get our hands on new copies — a regrettably infrequent occurrence — the wartime shellac is of such poor quality that surface noise remains at a very high level. We have here done everything possible to reduce such extraneous noise to a minimum without sacrificing the warmth and presence of the original sound.

Django Reinhardt always harboured an avowed weakness for big bands. Even in the 1930s he grabbed every available opportunity to play in large outfits, and subsequently never lost a chance to assemble one of his own. After the war, he was delighted to be engaged by Duke Ellington, just as he must have been back on 8 May1942 when, once again in Brussels, he found himself in the company of a symphony-style jazz outfit. Led by a pioneer of Belgian jazz, Stan Benders, this was no doubt the country’s most famous big band of the Occupation years.

The presence of a sizeable string-section, far from making the orchestra syrupy, imparts a strange, ethereal atmosphere to the first three titles recorded that day: Djangology, an old hit of Django’s; Begin The Beguine, a popular American piece discreetly translated into French for the occasion; and Nuages, a Django masterpiece already recorded twice in the autumn of 1940, the year it was composed. This particular version of Nuages is arguably the best of the lot.

So attractive do these three performances turn out to be, it seems almost a pity to lose the strings for the ensuing five titles, although true they would have been less at home on what is material of more traditional hue. Indeed, Django Rag is a barely disguised version of the rip-roaring Tiger Rag, while Chez Moi à six Heures is very much in the swinging Count Basie manner.

At this same session, Hubert Rostaing was once again summoned into action to record a few sides of his own, among them Hésitation and Mohican, the latter a conveniently oblique reference to America. The selfsame America that would at last have the opportunity of hearing his partner, Django, in the flesh in 1946 and 1947, although the guitarist would subsequently prefer to limit his travels to heading south for Italy, or even northwards back to Brussels.

Django Reinhardt’s forays into foreign lands were by now severely numbered, however, for destiny had marked him down for premature death. He died on 15 May 1953, a mere 43 years old. Fifteen years later, the town council of his native Liberchies discussed the idea of erecting a plaque or even a monument in his memory. But that’s as far as they got, the project subsequently abandoned for what was officially described as “lack of funds.”

Adapted from the French by Don Waterhouse

Contrairement aux deux premiers volumes de cette collection, qui présentent Django Reinhardt dans son cadre "habituel" —celui du Quintette à cordes du Hot Club de France avec Stéphane Grappelli— ce troisième album le trouve en compagnie de la plupart des grands solistes noirs américains qui jouèrent en France entre 1935 et 1940. Il manque cependant Louis Armstrong, qui vint à Paris en 1933-34, mais qui ne fit pas de disques avec Django. Il manque aussi Duke Ellington, qui, avec son orchestre, donna des concerts Salle Pleyel en 1933; lui, ne fera appel à Django qu'après la guerre. Par contre, lors de la seconde tournée européenne de la formation au printemps de 1939, quelques-uns de ses membres (Rex Stewart, Barney Bigard, Billy Taylor) acceptèrent d'enregistrer quelques très belles faces en quartette avec lui comme quatrième. Trois d'entre-elles, Finesse, I Know That You Know et Solid Old Man figurent ici en bonne place.

Un trompettiste comme Arthur Briggs, arrivé en Europe dès 1919 et qui n'est quasiment jamais reparti, pouvait déjà être considéré comme un vieux Parisien dans les années 30! Il avait déjà fait des tas de disques sous son nom en Allemagne à la fin des années 20, puis avait continué en France, soit avec le grand orchestre qu'il co-dirigeait avec le pianiste Freddy Johnson, soit avec des unités plus réduites ou des formations de studio dans lesquelles Django avait son mot à dire. Scatterbrain a été enregistré par l'une d'elles pendant la "drôle de guerre", Briggs ayant, contrairement à la plupart de ses collègues, décidé de ne pas quitter le France. Il est également présent, cinq ans plus tôt, dans Blue Moon, au sein d'un orchestre dirigé par le violoniste Michel Warlop et chargé d'accompagner celui que l'on avait appelé le "Père du saxophone ténor", Coleman Hawkins, désireux et ravi lui aussi de voir du pays. Star Dust, enregistré par lui en petite formation date du même jour. De 1934 à 1939, Hawkins joua en Angleterre, en Suisse, en Hollande, en Belgique, en Suède, en France… Il enregistra dans presque tous ces pays mais sa plus belle séance européenne demeure sans doute celle, parisienne de nouveau, du 28 avril 1937. Son vieux copain Benny Carter, saxophoniste, trompettiste, compositeur, arrangeur, s'était à son tour exilé et il savait merveilleusement écrire pour un quatuor de saxophones. On lui passa commande, mais il n'eut pas assez de temps, et seul Honeysuckle Rose fut réalisé dans cet esprit : deux altos, deux ténors, deux Américains (Carter, Hawkins), deux Français (André Ekyan, Alix Combelle). Le résultat est superbe d'élégance et Django se révèle accompagnateur d'élite. Crazy Rhythm, avec les mêmes quatre saxophonistes, est surtout une suite d'excellents solos.

Hawkins et Carter restèrent l'un et l'autre plusieurs années en Europe et y firent, parfois ensemble, souvent séparément, de nombreux disques. En 1938, juste avant de rentrer à la maison, Carter fit trois nouvelles faces avec une partie de son orchestre, auquel on ajouta Alix Combelle et, bien entendu, Django. On avait l'intention de renouveler dans I'm Coming Virginia, Farewell Blues et Blue Light Blues le coup du quatuor de saxophones, malgré l'absence de Coleman Hawkins. Cela ne marcha qu'en partie, mais les trois morceaux sonnent agréablement et le guitariste, rythmicien (et parfois soliste) exemplaire, parvient à imposer un tempo d'acier. Parmi ceux qui avaient également forte envie de ne plus quitter l'Europe, on trouve encore le très raffiné trompettiste Bill Coleman. Son plus grand désir, depuis l'enfance, était de venir à Paris. Il eut la chance de le réaliser plusieurs fois et même, après la guerre, d'en faire enfin sa résidence principale! Arrivé en 1935 il y joua beaucoup (surtout avec l'orchestre de Willie Lewis), mais se produisit également en Belgique, en Hollande, en Suisse, en Afrique du Nord et même en Egypte. A Paris, on lui fit faire pas mal de disques, dont quelques-uns avec Django. Swing Guitars, une composition du guitariste et de Stéphane Grappelli, et Bill Coleman Blues comptent parmi les meilleurs.

Bill Coleman fut également requis par son vieil ami le trombone Dicky Wells, lors du passage de ce dernier, alors membre de l'orchestre de Teddy Hill. Pendant l'été 1937, cette formation vint à Paris accompagner au Moulin Rouge la revue du "Cotton Club" et Wells, considéré comme le meilleur soliste, accepta de faire quelques disques sous son nom, dont Bugle Call Rag, Hangin' Around Boudon et Japanese Sandman. Là encore, surtout dans les morceaux en petite formation, Django se montra à la hauteur de sa réputation. Dicky Wells et la troupe du Cotton Club n'étaient que de passage, comme Duke Ellington en 1933 et 1939. Par contre Arthur Briggs, Benny Carter, Coleman Hawkins, Bill Coleman désiraient rester, et seule la guerre imminente fit changer d'avis les trois derniers cités. Quelques autres moins connus se trouvèrent dans le même cas : les pianistes Ray Stokes, Freddy Johnson, Charlie Lewis (ce dernier parvint à passer toute l'Occupation à Paris sans être inquiété!) et le saxophoniste de la Nouvelle Orléans Frank "Big Boy" Goudie. Django joua également en leur compagnie (Stokes, par exemple, est présent dans le Scatterbrain de 1940) et parfois les accompagna dans leurs séances de disques (voir le Saint Louis Blues de Goudie ici même).

Entre ces presque sédentaires et les itinérants, on peut placer le très délicat violoniste noir Eddie South, qui joua à Chicago dans les années vingt et qui, de formation classique, vint ensuite se perfectionner en Europe, notamment à Budapest et à Paris. Il voyagea donc beaucoup et essaya de rester dans chaque lieu qui l'intéressait plus longtemps que ceux simplement soumis au hasard des tournées. Passionné de musique tzigane, il accepta avec joie d'enregistrer avec Django en 1937, alors qu'il se trouvait à Paris à l'occasion de l'exposition universelle. Non seulement ces deux superbes virtuoses qui étaient faits pour se rencontrer surent d'emblée trouver la bonne carburation sur des airs aussi fameux que Sweet Georgia Brown ou I Can't Believe That You're In Love With Me mais, de surcroit, South eu le plaisir de se mesurer avec les deux spécialistes français du violon, deux des partenaires de prédilection de Django d'ailleurs : Michel Warlop et surtout Stéphane Grappelli (Lady Be Good).

Fin 1939, début 1940, presque tous les amis américains jugeront plus prudent de regagner leur pays. Ceux qui resteront seront, pour la plupart internés dans des camps jusqu'à la Libération ou se verront dans l'obligation de se cacher. Dans ces conditions, plus question de faire le bœuf dans les studios ou dans les petits bistrots sympas de Montmartre. Django aussi devra attendre la Libération. Et, en 44-45, il retrouvera joyeusement quelques vieux copains et bon nombre de nouveaux venus, dont certains pratiquant déjà un style tout neuf baptisé "bebop".

Unlike the two opening volumes of this collection, both of which present Django alongside Stéphane Grappelli in the more usual context of the Quintet of the Hot Club of France, this third album finds him in the company of most of the top black American solists operating in France between 1935 and 1940. Missing from the party, regrettably, are two of the biggest names in jazz : Louis Armstrong, who during his 1933-34 visit to Paris did not get round to making any records with Django; and Duke Ellington, who played at Paris' Salle Pleyel in 1933 and toured Europe again in the spring of 1939, but did not actually work with Django until after the war.

During that 1939 trip by Duke's men, however, three of his leading soloists —Rex Stewart, Barney Bigard and Billy Taylor— visited the Paris studios to cut a handful of wonderful sides in quartet format. The man they chose to turn three into four was… Django. Finesse, I Know That You Know and Solid Old Man are from that outstanding session.

Trumpeter Arthur Briggs had first come to Europe as early as 1919, and, apart from one or two brief breaks, would stay there the rest of his life. Which meant that by the 1930s he could almost consider himself a seasoned Parisian. He had already cut a whole pile of records in Germany in the late 'twenties, and he continued his recording activity in France, either as co-leader of a big band with pianist Freddy Johnson, or as member of small pick-up groups of which Django also was frequently in the ranks. Scatterbrain was recording at one such session during the early days of the war, Briggs being one of those hardy Americans not to flee for home. Five years earlier, he had also been present alongside Django in an orchestra led by violonist Michel Warlop when they recorded Blue Moon as accompanying group to the visiting "Father of the Tenor Saxophone", Coleman Hawkins.

Indeed, Hawkins was yet another eminent American to acquire a taste for Europe, and on that same March 1935 day, with the highly respected Django still in the line-up, he recorded a quintet version of Star Dust. Between 1934 and 1939 Hawkins played in England, Switzerland, Holland, Belgium, Sweden and France, leaving behind him a whole trail of recordings. But his finest European session, without a doubt, took place in Paris on 28 April 1937. His old friend Benny Carter —a saxophonist, trumpeter, composer and arranger who had also happily exiled himself in Europe— accepted a commission to score four pieces for recording by a saxophone quatuor. Renowned for his skills at voicing saxophones, Carter unfortunately did not have sufficient time to write all the necessary parts, and in the end only Honeysuckle Rose received the intented treatment. Two altos and two tenors, two Americans (Carter and Hawkins) and two French (André Ekyan and Alix Combelle), produced a performance memorable for its supreme elegance, with Django a model of musicality. When the same group tackled Crazy Rhythm, it made a fine job of what is in effect a string of excellent solos.

Hawkins and Carter both spent many years in Europe, turning out a considerable number of records, sometimes together, often apart. In 1938, just before heading for home, Carter cut three further sides, using a contingent from his orchestra plus Alix Combelle and Django. With I'm Coming Virginia, Farewell Blues and Blue Light Blues, the idea was to repeat the saxophone-quatuor formula, despite the absence of Hawkins. The results proved only a partial success, but all three pieces still sound pretty good by any ordinary standarts and Django, whether as solid section-player or inspired soloist, is exemplary.

Among those other Americans who, once in Europe, showed no desire to return home was that delightfully refined trumpeter, Bill Coleman. Born in Paris, Kentucky, his overriding ambition from childhood had been to come to Paris, France. Not only did he succeed in making several prewar stays in the French capital from 1935 onwards, but after the war he made France his permanent home. When in Paris he played mostly in the Willie Lewis Orchestra, but he also took time to fulfil engagements in Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, French North Africa and even Egypt. He made numerous records in Paris, often with Django. Swing Guitars, co-composed by Django and Stéphane Grappelli, and Bill Coleman Blues rank among their best work together.

Bill Coleman was also pressed into service by his old friend, trombonist Dicky Wells, when the latter visited Paris in the summer of 1937 as member of the Teddy Hill Orchestra, in town to accompany the Cotton Club Revue at the Moulin Rouge. Wells, considered the band's outstanding soloist, was invited to record under his own banner. Three of the sides those sessions produced are Bugle Call Rag, Hangin' Around Boudon and Japanese Sandman. Once again, Django fully justifies his reputation, especially on the pieces cut by the smaller group.

The Teddy Hill Orchestra with Dicky Wells, like the Duke Ellington aggregation in 1933 and 1939, was only passing through Paris. Arthur Briggs, Benny Carter, Coleman Hawkins and Bill Coleman, on the other hand, were sufficiently installed in Europe to want to stay on. The imminence of war, however, caused all of them but Briggs to head for home. A few less familiar personalities found themselves in the same dilemma : among them, pianists Ray Stokes, Freddy Johnson and Charlie Lewis (although Lewis stayed in France throughout the war without being troubled!), and New Orleans reedman Frank "Big Boy" Goudie. Django was one of their frequent musical companions (he is present on the 1940 Scatterbrain, for example), and they were never reluctant to invite him into the line-up of any of the groups they themselves fronted, witness the Goudie Saint Louis Blues session.

Somewhere between the Paris regulars and the mere visitors was black violinist Eddie South. Of classical training, South had played in Chicago in the 'twenties, then came to Europe to perfect his technique, notably in Budapest and Paris. He thus travelled a lot, but, instead of letting touring schedules run his life, he always strove to settle for longer spells in the cities that interested him most. Passionately fond of gypsy music, he was delighted to have the opportunity of recording with Django in 1937 when he was in Paris for the Universal Exhibition. Not only did these two superb, eminently compatible, virtuosos instantly prove a perfect match on famous pieces such a Sweet Georgia Brown and I Can't Believe That You're In Love With Me, but South at the same time found himself with a chance to measure up to two of France's top violonists, both good friends of Django's, Michel Warlop and Stéphane Grappelli (Lady Be Good).

In late 1939 and early 1940 most remaining Americans decided it was high time to get out of France and head for the sanctuary of their home country. The few who remained, with just a couple of lucky exceptions, were either interned or forced to remain in hiding. Gone now were the days of Franco-American jam sessions in the recording studios or in appealing little Montmartre nightspots, which meant Django's challenging jousts with American jazzmen went into hold until the Liberation.

By 1944-45 the guitarist was beginning once again to meet up with one or two old buddies, plus a few new ones as well. And some of these were by this time practising a strange new style by the name of bebop.